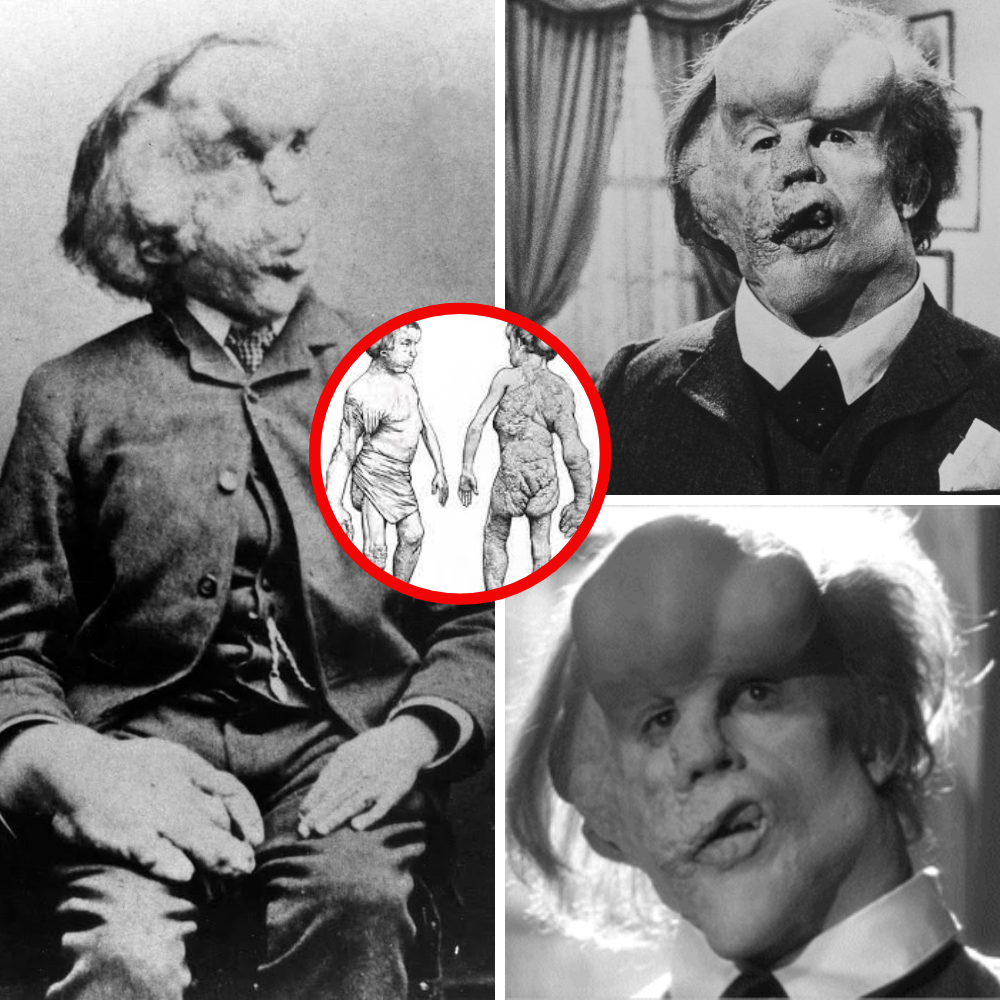

Joseph Carey Merrick, the real-life figure immortalized as “The Elephant Man,” endured a lifetime of unimaginable physical torment and societal scorn in 19th-century England, only to emerge in his final years as a poignant emblem of resilience and the human spirit.

Born on August 5, 1862, in the gritty industrial slums of Leicester, England, to a poor furniture-maker father named Joseph Rockley Merrick and a mother, Mary Jane, who worked as a cigarette maker, young Joseph entered the world seemingly unremarkable. But by age 2, his body began a grotesque transformation that would define—and nearly destroy—his existence. His skin thickened into rough, grayish lumps resembling an elephant’s hide; his limbs swelled asymmetrically, one arm ballooning to twice the size of the other; and his jaw protruded grotesquely, rendering eating a laborious ordeal. Most heartbreakingly, his skull expanded unevenly, forcing his head to weigh nearly 14 pounds and hang forward, making sleep impossible in a conventional position. “I am the happiest man alive,” Merrick would later pen in a poignant pamphlet, but those words masked profound isolation.

Contemporary theories pinned his condition on a freak accident—rumors swirled that his mother had been frightened by an escaped circus elephant during pregnancy, cursing the child with “maternal impression,” a now-debunked Victorian pseudoscience. Modern pathologists, analyzing his preserved skeleton at Queen Mary University of London, lean toward Proteus syndrome, a rare genetic disorder causing uncontrolled tissue overgrowth, or possibly a combination with neurofibromatosis. Whatever the cause, Merrick’s deformities escalated rapidly. By age 5, his skin had turned “thick and lumpy, like that of an elephant, and almost the same color,” as he described in his self-penned autobiography. Schoolmates tormented him relentlessly, pelting him with stones and chanting cruel epithets, forcing his withdrawal from education at age 10.

Home offered no refuge. When Merrick’s mother died in 1870, possibly from respiratory issues exacerbated by her own scoliosis, his father remarried a woman who viewed the boy as a burdensome “monster.” At 11, Merrick was ejected from the household and shuttled into a brutal workhouse, where he toiled in the bone-crushing grind of Leicester’s factories. His misshapen hands—fingers fused and elongated—proved useless for fine labor, and he was dismissed after mere weeks. Desperation peaked at 17 when, hawking cheap leather handbags on street corners to survive, he was beaten and robbed by thugs, leaving him homeless and hopeless. “I was like a wild beast,” he recalled, contemplating suicide by drowning in the Grand Union Canal but pulling back at the last moment.

Salvation, of a twisted sort, arrived in 1884 via the seedy underbelly of Victorian entertainment: the freak show circuit. Showman Sam Torr spotted Merrick’s potential and billed him as “Half-Man, Half-Elephant,” fabricating a lurid backstory tying his afflictions to that mythical prenatal elephant trampling. Merrick’s act exploded in popularity. Touring Midlands towns like Nottingham and Birmingham, he was displayed in dimly lit tents, shrouded in a hooded cloak to heighten the reveal. Audiences gasped at his unveiling: a 5-foot-2 figure with a torso like weathered bark, legs bowed like ancient oaks, and a face obscured by a pendulous “trunk” of flesh dangling from his upper lip. For 2 pence, spectators could gawk, poke, and whisper; Merrick, ever polite, recited poetry or built intricate cardboard cathedrals to fill the awkward silences. Earnings peaked at £200 a week—lavish for the era—but exploitation shadowed every penny. Managers pocketed most, and Merrick endured constant harassment, including a savage mob attack in a Lancashire train station that fractured his hip.

By 1886, Merrick had landed in London’s East End, the heart of Whitechapel infamy amid Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror. At a garish penny gaff on Whitechapel Road—decorated with Hitchcockian posters of a tusked abomination—he drew crowds of slum-dwellers, sailors, and thrill-seekers. It was here, in August of that year, that fate intervened through an unlikely savior: Dr. Frederick Treves, a ambitious young surgeon at the nearby London Hospital. Treves, lecturing on anatomy at the Pathological Society, had heard whispers of this “medical marvel” and paid a shilling for a private viewing. What he found wasn’t a beast but a gentle soul: Merrick, barely audible through his malformed mouth, greeted him with “Thank you, sir, for your kindness.” Treves arranged for Merrick’s relocation to the hospital’s attic rooms, free from the freak-show grind, under the guise of a research subject. It marked the end of his public degradation—and the dawn of a fragile dignity.

Life at London Hospital transformed Merrick. Treves, initially clinical, grew paternal, shielding him from gawking donors and nosy press. Merrick received tailored suits, learned to “sleep like a man” by propping his head on a custom harness, and devoured books with voracious appetite—Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the Bible, even romantic novels. His intellect shone: He composed poetry, sculpted wax models, and penned letters begging Queen Victoria for a home in the countryside, dreaming of normalcy. “All I wanted was to be like everybody else,” he confided to a nurse. Society’s elite, drawn by Treves’ discreet invitations, visited in droves. Actress Madge Kendal brought theatrical costumes for dress-up games; Alexandra, Princess of Wales (later Queen consort), gifted him a monogrammed shaving kit. These encounters—tea with luminaries, theater outings in veiled anonymity—offered glimpses of acceptance, though Merrick remained painfully aware of his otherness. “I am not an animal,” he once pleaded, echoing the hospital’s dehumanizing whispers.

Yet tragedy loomed. Merrick’s body, ravaged by decades of unchecked growth, rebelled. His scoliosis twisted his spine into a near-90-degree curve; respiratory infections plagued his labored breathing. On April 11, 1890, just shy of his 28th birthday, attendants found him dead in his sleep—erect, as if attempting to “die like a man” by defying his neck’s weakness. Treves’ autopsy revealed a dislocated neck vertebra, crushed under his massive head’s weight, causing asphyxiation. Even in death, exploitation persisted: Treves cast his torso in plaster, sampled his skin for “study,” and mounted his bleached skeleton for display—a fate Merrick had explicitly rejected. His remains were unceremoniously buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at City of London Cemetery until rediscovered in 2019, prompting calls for a dignified reburial.

Merrick’s legacy, however, transcends the macabre. Treves’ 1923 memoir, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences—riddled with errors, like dubbing him “John”—sparked a cultural firestorm. In 1979, Bernard Pomerance’s Tony-winning play The Elephant Man premiered on Broadway, with Bradley Cooper later reviving it in 2014, stripping actors of makeup to emphasize Merrick’s inner humanity. David Lynch’s haunting 1980 black-and-white film, starring John Hurt in prosthetic agony and Anthony Hopkins as Treves, earned eight Oscar nods and grossed $26 million on a shoestring budget. Hopkins’ measured intensity here even influenced his chilling Hannibal Lecter in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs. Documentaries, like the 1997 BBC special narrated by Hurt, and books such as Michael Howell and Peter Ford’s 1980 corrective The True History of the Elephant Man, have peeled back myths to reveal Merrick’s sharp wit and unyielding politeness.

Today, Merrick’s story resonates amid debates on disability rights and eugenics’ dark echoes. His Leicester birthplace sports a heritage plaque; descendants like Patricia Selby, a great-niece, cherish family lore of his “very nice” nature. Biographer Joanne Vigor-Mungovin, whose 2019 book The Man Who Was Merrick explores his Leicester roots, notes ongoing efforts for a memorial. On X (formerly Twitter), his tale sparks reflections: A recent post marked the 45th anniversary of Lynch’s film, tying it to Merrick’s enduring fight against dehumanization. Another hailed a 1997 doc as “brilliant,” underscoring his global pull.

In an age of filtered facades and snap judgments, Merrick’s tragedy indicts a society’s capacity for cruelty—and its potential for redemption. He sought no pity, only parity: “It is some consolation… that I am not entirely useless.” Over a century later, his words challenge us: What does it mean to truly see the “other”? Merrick’s answer—delivered through a lifetime of quiet grace—remains a mirror to our souls.

News

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load