A heartfelt, unsent letter from 1968, penned by one of the Statler Brothers to their idol Johnny Cash, resurfaced decades later during a tour, symbolizing the mentorship and mutual respect that launched the quartet’s enduring career in country and gospel music.

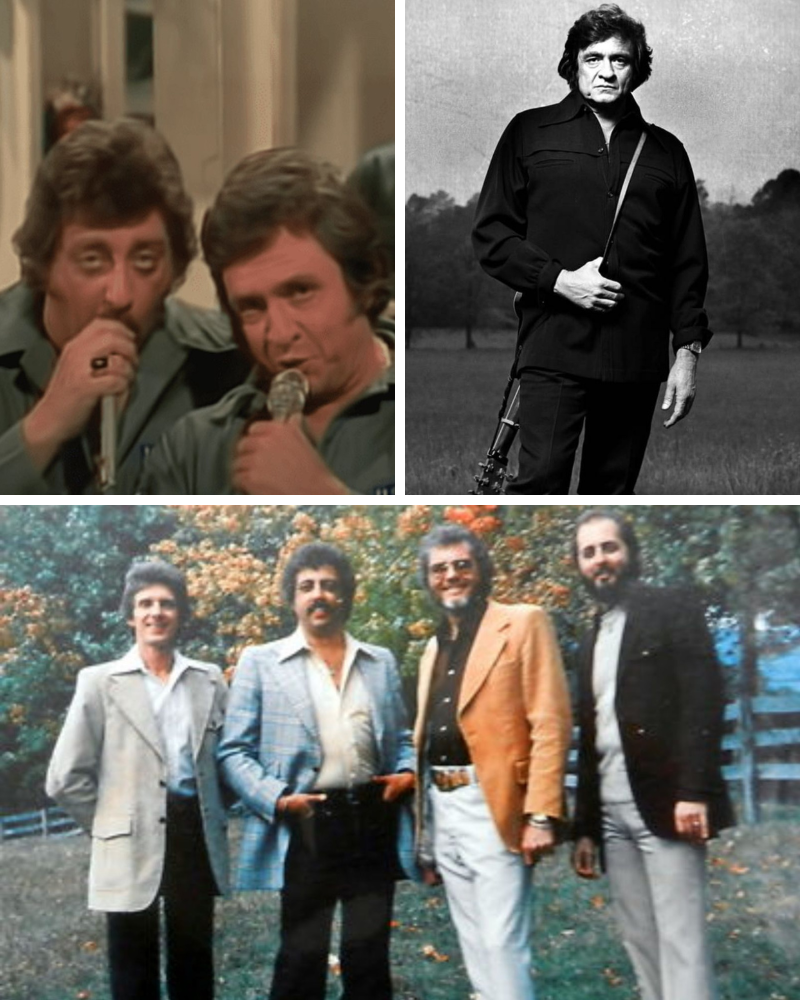

The Statler Brothers—Don Reid, Harold Reid, Phil Balsley, and Lew DeWitt—began as a gospel group in Staunton, Virginia, performing under names like the Four Star Quartet before adopting their signature moniker in 1963. Their big break came in 1964 when they caught the ear of Johnny Cash at a Roanoke concert. Cash, impressed by their harmonies despite never hearing them perform, invited the untested group to open for him in Berryville just days later. That handshake deal led to an eight-year stint as his opening act and backup singers, a period immortalized in their tribute song “We Got Paid by Cash.” The Reids, actual brothers from a musical family, infused the group with tight-knit Southern gospel roots, blending it seamlessly with country storytelling that would define their sound.

Harold Reid, the bass singer and de facto leader known for his humor and songwriting, was the one who drafted the letter in 1968. At the time, the Statlers were riding high on their breakthrough hit “Flowers on the Wall,” a quirky No. 2 Billboard country and pop crossover that earned two Grammys and a place in the Grammy Hall of Fame. But amid the whirlwind of fame, Harold penned a personal note to Cash from a church basement in Staunton, expressing awe at the Man in Black’s influence. “If we ever get half as good as you, we’ll still be twice as lucky as most,” the letter read, capturing the quartet’s humility and gratitude. Too self-conscious it might come across as overly sentimental, Harold tucked it away in his guitar case, where it gathered dust as an unmailed secret.

The letter’s journey took a poetic turn during one of the Statlers’ joint tours with Cash in the early 1970s. While preparing for a post-show meetup, Harold rediscovered the faded envelope amid his gear. With the confidence of years on the road together—backing Cash on albums like At Folsom Prison (1968) and appearing on The Johnny Cash Show from 1969 to 1971—he decided to share it. Handing the note to Cash backstage, Harold watched as the legend read it in silence, his weathered face softening. Cash looked up and replied simply, “You boys already are.” The words, delivered with Cash’s signature gravitas, affirmed not just their talent but the deep camaraderie that had formed. That exchange, recounted in family lore and Statler memoirs, turned the unsent letter into a cherished artifact, now framed in the Reid family home in Staunton—a reminder of mentorship’s quiet power.

The Statler Brothers’ association with Cash was more than professional; it was transformative. Cash, fresh off his own comeback with the Folsom Prison album, saw in the quartet a reflection of his gospel leanings and raw authenticity. The Statlers provided lush harmonies on tracks like “How Great Thou Art” from the live recording, their voices weaving through Cash’s baritone like threads in a quilt. In return, Cash’s endorsement opened doors at Columbia Records, where producer Jerry Kennedy helmed their early sessions. “Flowers on the Wall,” written by DeWitt, poked fun at loneliness with lines about “countin’ flowers on the wall that don’t bother me at all,” sleepin’ my life away”—a lighthearted escape that masked the group’s deeper gospel core. Their albums consistently featured faith-based songs, paying homage to influences like the Blackwood Brothers, whose style shaped their four-part blends.

By the mid-1970s, the Statlers parted ways with Cash on amicable terms to focus on their solo trajectory, but the bond endured. They penned “We Got Paid by Cash” as a playful nod to their benefactor, with lyrics thanking him for the “salary” of wisdom and opportunity: “We got paid by Cash, and we ain’t complainin’.” The song appeared on their 1975 album Holy Bible-Old Tyme Gospel Hour, blending humor with heartfelt tribute. Cash, in turn, praised their work in liner notes and interviews, calling them “the best harmony group in the business.” This mutual respect fueled the Statlers’ longevity, leading to over 50 albums, multiple No. 1 country hits like “Do You Know You Are My Sunshine” (1978) and “Elizabeth” (1984), and a 1991-1998 run hosting The Statler Brothers Show on The Nashville Network—the highest-rated program on the cable outlet.

Harold’s letter, though never mailed in ’68, encapsulated the era’s spirit: a time when country music bridged gospel humility with rising stardom. The 1960s saw Cash revitalizing the genre with raw, prison-recorded authenticity, while acts like the Statlers brought polished quartets to the forefront, influencing later groups like the Oak Ridge Boys. The unsent note’s rediscovery highlighted Harold’s multifaceted role—not just as the booming bass voice on hits like “Bed of Rose’s” (1970), a tale of redemption wrapped in wordplay, but as the group’s emotional anchor. His comedy sketches, often performed as alter ego Lester “Roadhog” Moran on parody albums like Alive at the Johnny Mack Brown High School (1974), added levity to their sets, earning Grammy nods for vocal group and comedy alike.

The Statlers’ career spanned four decades, retiring in 2002 after a farewell tour that drew sellouts across the U.S. They were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2008, with Harold accepting alongside surviving members Don Reid, Balsley, and Jimmy Fortune, who replaced DeWitt in 1982. Tragically, Harold passed away on April 24, 2020, at 80 after battling kidney failure, leaving a legacy of 33 No. 1 singles and countless fans who cherished their clean, family-friendly appeal. Don Reid, now in his 80s, still resides in Staunton, preserving artifacts like the framed letter as touchstones of their journey.

Cash, who died in 2003, left an indelible mark on the Statlers, much as they did on him. Their collaborations, including duets on “This Old House” and gospel standards, showcased a synergy of gravelly truth-telling and soaring harmonies. The letter’s story resurfaced in tributes following Harold’s death, with Fortune recalling in interviews how Cash’s encouragement “gave us wings.” In Staunton, where the group hosted massive July 4th “Happy Birthday U.S.A.” concerts from 1970 to 1995—drawing up to 100,000 attendees—the letter symbolizes roots that never faded. Local fireworks lit the sky near Harold’s Boxley Farm the night he passed, an unplanned echo of those celebrations.

Today, the Statler Brothers’ music endures on streaming platforms and SiriusXM’s Outlaw Country channel, their gospel-country fusion inspiring modern acts like Little Big Town. The unsent letter, a snapshot of wide-eyed ambition, reminds us that true mentorship transcends fame—it’s in the quiet affirmations that echo for generations. As Don Reid reflected in a 2013 interview, “Johnny didn’t just hire us; he believed in us before we believed in ourselves.” Framed in a family home, that ’68 note stands as proof: sometimes, the messages worth sending are the ones that find their way anyway.

News

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

Rihanna made headlines again this week after reportedly leaving her home island of Barbados and returning to New York City for one purpose: to support and surprise A$AP Rocky at the release party for his new album Don’t Be Dumb.

According to individuals who attended the event, the singer arrived quietly and without advance notice, stepping into the venue just…

The pop music world was shaken this week after reports emerged that Rihanna has publicly refused to wear the LGBT rainbow armband at several upcoming high-profile events.

According to circulating accounts, the artist defended her decision with a firm explanation, stating that performance events should remain focused…

End of content

No more pages to load