The Nearline Pipeline Trail snakes like a forgotten vein through the thick Acadian wilderness of Pictou County, a gravel-laced corridor where towering black spruces claw at the sky and the underbrush devours light. It’s a place where secrets could hide forever—amid the tangled alder, the rusting train tracks paralleling its edge, and the peat bogs that swallow boots whole. On May 3, 2025, just 24 hours after six-year-old Lily Sullivan and her four-year-old brother Jack disappeared from their family’s ramshackle trailer on Gearlock Road, volunteer searcher Marissa LeBlanc froze in her tracks. There, pressed into the soft, rain-sodden mud beside the pipeline’s service path, was a single footprint. Child-sized. Barefoot. Pointing north, deeper into the shadows.

LeBlanc snapped photos, marked the spot with orange flagging tape, and radioed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). “It looked fresh,” she later told reporters, her voice trembling. “Like whoever made it was running—or being carried.” The print was cast in plaster, measured (barely seven inches long), and cataloged. But then? Nothing. For 28 agonizing days, it sat in evidence logs, dismissed as irrelevant or perhaps a red herring from one of the dozens of searchers tromping the area. Until May 31, when over 115 volunteers and RCMP officers swarmed back to the site, combing the pipeline’s edges with renewed fury. Why the delay? What deadly secret does that solitary mark hold? As winter’s chill descends on Nova Scotia six months later, with no sign of the children, that footprint has become the epicenter of a mystery that’s tearing families apart, fueling wild theories, and exposing cracks in the investigation that whisper of something far darker than a simple wandering gone wrong.

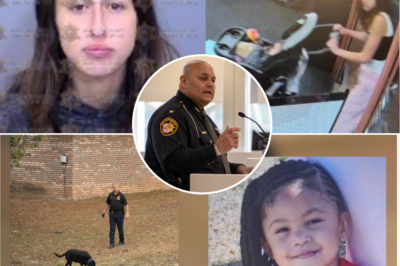

Lily and Jack’s disappearance on May 2, 2025, shattered the quiet hamlet of Lansdowne Station, a speck on the map 140 kilometers northeast of Halifax, where logging trucks rumble past weathered trailers and the forest presses in like an uninvited guest. The siblings—Lily with her wide, curious eyes and love for giraffes, Jack with his infectious grin and fascination with dinosaurs—lived with their mother, Malehya Brooks-Murray, her partner Daniel Martell (Jack and Lily’s stepfather), and a younger half-sibling. It was a modest life in a home described by neighbors as “cluttered but loving,” though whispers of domestic tensions simmered beneath.

That fateful morning dawned crisp and ordinary. Brooks-Murray told police she heard the children playing in the yard around 9 a.m., their laughter mingling with the birdsong. She stepped inside briefly—to change the baby, she said—and when she returned, silence. The sliding door hung ajar. No screams. No signs of struggle. Just absence. Lily’s pink boots and strawberry backpack? Gone. Jack’s blue dinosaur boots? Vanished. A frantic 911 call at 10 a.m. unleashed hell: “My babies are missing! Please, they were just here!”

Within hours, the largest search in Pictou County’s history mobilized. One hundred sixty volunteers, cadaver dogs with noses like radar, drones buzzing overhead, helicopters chopping the air with thermal cameras. They scoured 5.5 square kilometers of hurricane-scarred woods—ravines steep as cliffs, roots twisting like snares. Divers probed Lansdowne Lake’s murky depths. But nothing. No shredded clothing, no dropped toys, no scent trails for the hounds to latch onto. By May 7, the RCMP scaled back, their press conference grim: “Survival in these conditions for children this young is unlikely.” Staff Sergeant Rob McCamon, the face of the investigation, reiterated it was a missing persons case—no evidence of foul play. Yet, the major crime unit was involved from day one, a detail that raised eyebrows.

As days bled into weeks, the footprint emerged as the first tantalizing clue. Spotted near Lansdowne Lake, just off the pipeline trail—a secluded artery accessible by ATV but hidden from casual eyes—it didn’t match the children’s described footwear. Lily’s pink boots had tread patterns like hearts; Jack’s dinosaurs left claw marks. This print was smooth, as if from a sock or bare skin. “It could be theirs if they lost their shoes,” one searcher speculated anonymously. “Or someone else’s entirely.” The RCMP’s initial dismissal? “Not a high-priority lead,” they said. But by late May, “new information” prompted the revisit. What was it? They wouldn’t say. Volunteers that weekend—June 1—combed the pipeline’s brush-choked edges, where smugglers might dump cargo or worse. Orange ribbons marked cleared ground, pink for Lily, blue for Jack. Still, nothing.

The pipeline itself adds layers of intrigue. Stretching through remote terrain, it’s a conduit for natural gas but also a shadow highway—near train tracks for quick escapes, clearings for hidden deeds. Lost-child statistics scream anomaly: 95% of kids aged 4-6 are found within 6.5 kilometers of home. Lily and Jack? Evaporated beyond that radius, or perhaps never left it. “If they wandered, we’d have found traces,” said Nick Oldrieve, executive director of volunteer group Please Bring Me Home, who led a November 15 search focusing on “misadventure/wandering.” Low water levels in creeks and ponds revealed no bones, no clues. “It’s like the earth swallowed them.”

But what if the earth didn’t? Theories swirl like autumn leaves. A May 28 RCMP bombshell: Surveillance footage placed Lily and Jack alive on May 1 at 3:17 p.m. in New Glasgow, 30 kilometers away, with “family members.” Healthy? Distressed? The force won’t specify the location, companions, or context. This shrank the disappearance window to 19 hours, contradicting an earlier April 29 timeline. Why the secrecy? They’ve pored over hours of video from Gearlock Road and New Glasgow, pleading for dash cams from April 28-May 2. Yet no Amber Alert—despite 85% success rates in Canadian abductions. “No evidence of abduction,” insists McCamon, even as witness statements from neighbors like Brad Wong and Justin Smith described a “loud vehicle” coming and going five or six times after midnight on May 2. “It stayed in earshot,” Wong said. But no surveillance corroborated it, so it’s unsubstantiated.

Digital footprints tease more. From April 28-May 2, the RCMP dissected the family’s phones: GPS pings, call logs, searches. By May 15, 355 tips and 50 interviews yielded a “partial picture,” but details are locked tight. In 2024, digital forensics solved 60% of Canadian missing persons cases. Here? Crickets. Brooks-Murray’s device, Martell’s—each a potential timeline. Deleted data often screams loudest. “The phones know more than they’re saying,” one true-crime podcaster quipped.

Trail cams add fuel. On May 20, neighbor Melissa Scott, eight kilometers away, surrendered five days of footage from seven cameras—some wooded, one driveway near the pipeline. She saw nothing odd, but the major crime unit wanted it all, predating the May 1 sighting. Tracing a vehicle? A shadow? The footprint’s maker? The pipeline’s proximity to tracks makes it a criminal’s playground—or grave.

Family dynamics crack the facade. Daniel Martell, the stepfather, told media he passed a polygraph, tears welling as he professed innocence. “I’d do anything to find them,” he said, voice breaking. But the RCMP won’t confirm the test—conducted privately or officially? Polygraphs measure stress, not truth; notorious liars like Ted Bundy aced them. Martell’s demeanor: calm, rehearsed, contrasting raw grief in cleared cases like the McCanns. And Brooks-Murray? One day post-disappearance, she fled Lansdowne with her infant, blocking Martell online, lawyering up, vanishing from view. No vigils, no pleas—until October 13, when she poured her heart on Facebook’s “Find Lilly and Jack Sullivan” page.

“As a mother, I love my children more than life itself,” she wrote, her words a gut-punch. “The longing for them to come home is greater than I could imagine. I ache to hold them, kiss them, breathe their scent.” She described trauma: crying at Gabby’s Dollhouse songs, seeing their favorite candies in stores. “The pure pain of not knowing has devastated my life.” She praised family, friends, and Please Bring Me Home’s November search, vowing, “I’ll never stop. Someone knows something—bring my babies home.”

Her plea came amid swirling rumors. A $15,000 reward (now part of a $150,000 cold-case fund) dangles for info. Paternal grandmother Belynda Gray spoke to CTV Atlantic in October: “It’s every grandparent’s nightmare. We need answers.” On Jack’s fifth birthday—October 29—a candlelight vigil in Stellarton drew dozens, lanterns floating skyward. “Light their way home,” organizer Brenda MacPhee said. But whispers persist: Family fight pre-disappearance? Martell’s past-tense slips? Brooks-Murray’s silence?

Community fractures show. Pictou County’s 43,000 residents are on edge—kids fear playing outside, parents lock doors. Warden Robert Parker: “Anxiety and frustration. How can two kids vanish without trace?” Over 10,000 search hours, 800 tips—no breakthrough. An October 8 search yielded zilch. Cadaver dogs in early October sniffed nothing. “No human remains,” Oldrieve confirmed.

True-crime sleuths dissect online: Reddit threads parse Martell’s interviews (“He knew clothing details he shouldn’t!”); TikTok videos zoom on Brooks-Murray’s “calm” demeanor. A YouTube doc from June—”Lily & Jack Sullivan: The Footprint’s Deadly Secret”—amassed 50,000 views, probing the print as a “confession waiting to break.” Experts like forensic psychologist Dr. Lena Voss: “Inconsistencies suggest cover-up—troubled home, delayed alerts.” But child advocate Mia Chen counters: “Don’t victim-blame. Remember the McCanns—innocent till proven.”

As snow dusts the pipeline, searches pivot to spring thaws. RCMP: “All possibilities open. Evidence leads us.” But six months in, that footprint mocks them—a tiny accusation in mud. Was it Lily’s, fleeing? Jack’s, carried? A stranger’s lure? Or planted diversion?

Lily’s giraffes, Jack’s dinosaurs—innocence lost. Pictou holds vigils, prays. But the pipeline’s shadows deepen. What lies along it? Answers? Bodies? Or a family’s unraveling truth?

News

😱 Police Celebration? Parents in Tears? The Explosive Headline About Madeleine McCann That’s Shaking Social Media 💔🌍

The headline screams across social media and tabloid feeds like a thunderclap after nearly two decades of agonizing silence: END…

🐑 After Fires, Tears, and Hard Work, Kelvin Fletcher and Liz Fletcher Celebrate Huge Farm Milestone — Fans Call It ‘So Deserved!’ 💕🔥

Big Smiles on the Farm — And Fans Are Loving Every Second! Kelvin Fletcher and His Wife Liz Fletcher Reveal…

🌈💗 After Months of Uncertainty, Maya Edmonds Shows Heartening Improvement — Hospital Team Celebrates Small but Powerful Victories

Behind Every Hospital Monitor Beep: The Unbreakable Spirit of Maya Edmonds – A Twelve-Year-Old Warrior’s Quiet Battle at the Royal…

⚠️💔 Room in Chaos, Hidden Items Recovered — Investigators Tight-Lipped on Key Find in Teen Tragedy

EXCLUSIVE: Teen Lovers Cherish Bean, 15, and Ethan Slater, 17, Found Dead in Holiday Park – Sleeping Pills Scattered Under…

😢🏔️ Tragic End on Snowdon: Best Friends Eddie Hill, 20, and Jayden Long, 19, Found Dead After Freezing Overnight Ordeal

Tragic End for Two Young Best Friends on Snowdon: Eddie Hill, 20, and Jayden Long, 19, Found Dead After Desperate…

⚠️👀 Inside Job? Key Suspect in Genesis Reid Case Tracked Just 3 miles from Her Home — Is the Truth Hiding Next Door?

EXPOSED: Cops Track Key Suspect in Genesis Reid Case to Location Just 2.5 MILES from Her Home – Whispers of…

End of content

No more pages to load