Imagine this: The sun dips low over the mist-shrouded tea plantations of Kerala’s Western Ghats, casting a golden haze across rolling hills that seem to stretch into eternity. You’ve splurged on what promises to be the dining experience of a lifetime—a gourmet meal suspended 150 feet above the earth, swaying gently in a glass-enclosed pod that offers panoramic views of one of India’s most breathtaking landscapes. The air is crisp, the aroma of spiced chai and sizzling tandoori chicken wafts through the cabin, and your family’s laughter mingles with the distant call of hornbills. It’s adventure tourism at its most intoxicating, a blend of luxury and thrill that lures intrepid travelers from across the globe.

Now, picture that idyll shattering in an instant. A mechanical groan echoes like thunder. The pod lurches, freezes mid-air, and suddenly, you’re not diners anymore—you’re prisoners of gravity, dangling precariously over a chasm where one wrong move could spell disaster. For Muhammed Safwan, his wife Thoufeena, and their two young children, this wasn’t a nightmare from a blockbuster thriller. It was Friday afternoon in the hill district of Idukki, and their dream outing had morphed into a two-hour descent into terror.

The incident at Southern Skies Aerodynamics’ flagship “Sky Dine” attraction has sent shockwaves through India’s burgeoning adventure tourism sector, raising urgent questions about safety, regulation, and the razor-thin line between exhilaration and existential dread. What began as a routine lunch reservation ended with a family scaling down a towering crane on ropes, guided by firefighters who themselves braved the heights. As details emerge, the story unfolds like a high-stakes drama: a tale of human resilience, bureaucratic blind spots, and the intoxicating allure of heights that can turn deadly in a heartbeat.

The Allure of the Heights: How Sky Dining Conquered Kerala’s Skies

To understand the harrowing events of November 28, one must first grasp the magnetic pull of sky dining—a concept that’s exploded in popularity worldwide, from the revolving restaurants of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa to the cliffside eateries of Peru’s Sacred Valley. In India, where adventure tourism is a $40 billion industry employing millions, innovators like Southern Skies Aerodynamics are pushing boundaries to capture a slice of the pie. Launched just months ago in the verdant embrace of Munnar, the Sky Dine experience was billed as “dining on the edge of heaven.” Perched atop a repurposed industrial crane retrofitted with a transparent dining pod, it promised diners an adrenaline-fueled feast 150 feet above the tea estates, where the only traffic jam is a flock of birds and the soundtrack is the whisper of wind through eucalyptus groves.

Kerala, often dubbed “God’s Own Country,” is no stranger to such spectacles. This southern state, with its labyrinthine backwaters, spice-scented markets, and mist-veiled hills, has long been a magnet for eco-tourists and thrill-seekers alike. Munnar, at the heart of Idukki district, is its crown jewel—a colonial-era hill station where British tea planters once sipped Darjeeling amid the clouds. Today, it’s a hotspot for zip-lining, paragliding, and wildlife safaris in the Eravikulam National Park, home to the endangered Nilgiri tahr. But Southern Skies aimed higher—literally. Their marketing pitch was irresistible: “Elevate your senses. Savor spice-kissed Kerala cuisine while the world falls away beneath you.” Reservations filled up weeks in advance, drawing families, honeymooners, and influencers eager to capture that perfect Instagram reel of samosas against a sunset skyline.

Muhammed Safwan, a 31-year-old software engineer from the coastal city of Kozhikode, had booked the slot as a belated anniversary surprise. “We wanted something memorable for the kids,” he later recounted to local reporters, his voice still laced with the tremor of recollection. Safwan and his wife, Thoufeena, 25, a schoolteacher with a passion for photography, had scrimped to afford the 5,000-rupee-per-head extravaganza. Their children—five-year-old Aisha, with her infectious giggle, and three-year-old Omar, a bundle of boundless energy—were buzzing with excitement as the family boarded a shuttle from their modest homestay in Munnar town. Little did they know, this meal would etch itself into their memories not for its flavors, but for the fight for survival that followed.

The Lunch That Never Landed: A Timeline of Terror

It was just past 1:15 p.m. when the Safwan family stepped into the Sky Dine pod—a sleek, cylindrical capsule of reinforced glass and steel, about the size of a luxury gondola, equipped with plush leather seats, a mini-bar, and a menu curated by a Mumbai-based Michelin-aspirant chef. The ascent was smooth, a hydraulic hum propelling them skyward like an elevator to the gods. At 150 feet, the pod locked into position with a satisfying click, and the real show began. Below, the tea gardens unfurled like an emerald quilt, dotted with workers in conical hats harvesting leaves under the relentless tropical sun. To the east, the Anaimudi Peak loomed, Kerala’s highest summit, a sentinel shrouded in perpetual fog.

The meal commenced with appetizers: crispy dosas stuffed with spiced potatoes, paired with coconut chutney and fresh lime soda. Conversation flowed easily—Safwan teasing Thoufeena about her fear of heights, Aisha pointing out shapes in the clouds, Omar demolishing his plate with the enthusiasm only a toddler can muster. Haripriya, the 28-year-old server assigned to their pod, fluttered about like a benevolent sprite, refilling glasses and regaling them with tales of Munnar’s colonial ghosts. A native of nearby Adimali, Haripriya had joined Southern Skies just weeks earlier, drawn by the promise of steady tips and the thrill of working at altitude. “It’s like being a bird,” she quipped, adjusting the pod’s ambient lighting to a warm amber glow.

Then, at approximately 1:30 p.m., disaster struck. Witnesses on the ground—fellow tourists picnicking in the adjacent viewpoint—described hearing a metallic screech, followed by an unnatural stillness. The pod, meant to gently rotate for 360-degree views, jolted to a halt. Safwan felt it first: a subtle vibration, then nothing. “I thought it was part of the experience, like a dramatic pause,” he admitted. But as minutes ticked by, unease crept in. Haripriya radioed the control booth, her voice steady but edged with concern. Static crackled back—no response.

Inside the pod, the atmosphere shifted from jovial to claustrophobic. The glass walls, once a window to wonder, now framed a vertiginous drop. Aisha pressed her face against the pane, her small fingers tracing the rivulets of condensation. “Mama, why aren’t we moving?” she asked, her voice a fragile thread. Thoufeena, fighting a rising wave of nausea, forced a smile. “It’s okay, baby. They’re just fixing a little glitch.” But her hands trembled as she clutched Omar, who had begun to fuss, sensing the tension like a barometer to parental fear. Safwan pounded on the emergency button, but the speakers emitted only silence. The pod swayed faintly in the breeze—a 10-mph gust that amplified every creak into a potential death knell.

Down below, chaos brewed in slow motion. The restaurant’s management, a skeleton crew of five led by a harried operations manager named Rajesh Kumar, scrambled in the control room. Alarms blared intermittently, but the hydraulic system—cobbled together from second-hand parts sourced from a Kochi scrapyard—had seized up. A suspected failure in the pressure valves, later pinpointed by investigators, had locked the winch mechanism. Kumar later claimed he attempted to override the system manually, but the controls were unresponsive. In a baffling lapse, no immediate call to emergency services was made. “We didn’t want to alarm the guests unnecessarily,” he told investigators, a statement that would later draw widespread scorn.

It was local residents who sounded the alarm. Among them was Lakshmi Nair, a 52-year-old tea estate supervisor whose afternoon break was interrupted by the sight of the immobilized pod glinting like a stalled star. “I saw the family inside—children waving, looking scared. The staff just stood there, gesturing futilely,” Nair recounted to The Hindu. Racing to her scooter, she alerted the nearest police outpost, igniting a chain reaction that would mobilize Kerala’s vaunted disaster response network.

Rescue at the Razor’s Edge: Heroes in Harness

By 2:00 p.m., whispers of the “dangling diners” had rippled through Munnar like wildfire. Social media buzzed with grainy smartphone videos—pods frozen mid-air, ground crews milling in confusion. The first responders arrived at 3:45 p.m.: a crack team from the Munnar Fire and Rescue Station, supplemented by specialists from Adimali. Led by Station Officer Praveen Kumar, a 15-year veteran with a chest full of medals from flood rescues in the 2018 Kerala deluge, the unit assessed the scene with practiced calm.

The setup was nightmarish. The crane, a 50-meter behemoth originally designed for construction in Mumbai’s shipyards, now stood as an unwitting villain. Its boom extended like a skeletal arm over uneven terrain, with the pod suspended at a precarious angle. Winds had picked up to 15 knots, causing the capsule to rock like a pendulum. “We had about 20 minutes of good light left,” Kumar explained in a debriefing. “Any delay, and we’d be operating in dusk with fatigued personnel.”

The rescue plan was audacious: a multi-stage rappel using industrial-grade kernmantle ropes, anchored to the crane’s apex. Firefighters, clad in harnesses and helmets fitted with headlamps, scaled the structure first—a vertical ascent that tested even their iron wills. At the pod, they breached the hatch with a hydraulic cutter, the screech of metal on metal drowned out by the family’s relieved sobs. “Hold on, we’re here,” shouted rescuer Anil Das, a 29-year-old father of two, as he clipped into the pod’s frame.

The descent was choreographed with the precision of a ballet on a tightrope. Priority went to the vulnerable: Aisha and Omar first, bundled into rescue slings and lowered in tandem, their tiny forms silhouetted against the fading sky. Thoufeena followed, her face pale but resolute, gripping the ropes as Das coached her breath by breath. “One foot at a time, ma’am. You’re doing brilliantly.” Safwan, ever the protector, insisted on going last with Haripriya, who had kept composure throughout by singing lullabies to the children. By 4:30 p.m., all five were on solid ground, greeted by a phalanx of medics and a crowd of relieved onlookers. A safety net, hastily deployed by civil defense volunteers, had caught stray gear but proved unnecessary for the human cargo.

In the medical tent, the family underwent checks for shock and dehydration. Miraculously, injuries were minor: a few scrapes from the harnesses, lingering vertigo for Thoufeena, and nightmares-in-waiting for the kids. “We hugged them so tight, we thought our hearts would burst,” Safwan said, tears mingling with sweat as he cradled his children. Haripriya, sporting a bruised elbow, waved off concern. “I’ve climbed worse in the cardamom hills back home. But those little ones—they’re the real heroes.”

Echoes of Neglect: Unraveling the Mechanical Mayhem

As the adrenaline ebbed, scrutiny turned to the “why.” Preliminary probes by the Devikulam Subcollector, V.M. Arya, revealed a litany of red flags. The hydraulic failure stemmed from a degraded seal in the crane’s lift cylinder—a component overdue for maintenance by six months, according to service logs obtained by India Today. Southern Skies, a startup founded by a trio of IIT graduates with dreams of “revolutionizing aerial hospitality,” had cut corners to meet launch deadlines. The crane, acquired for a bargain 20 lakh rupees, lacked the dual-redundancy systems standard in certified amusement rides.

More damning was the regulatory vacuum. Arya, in a terse statement to the press, admitted: “There are no specific guidelines for operating adventure tourism facilities like this in Kerala. It’s a Wild West up there.” India’s adventure sector, while booming—contributing 6.5% to GDP—operates in a patchwork of state-level rules, with national oversight fragmented between the Ministry of Tourism and the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India (ATOAI). Sky Dine, classified as a “novel experiential venue,” had slipped through the cracks, receiving only a cursory nod from the local panchayat.

Eyewitnesses painted a picture of institutional inertia. Residents like Nair lambasted the restaurant’s management for the hour-long delay in alerting authorities. “They were more worried about their reputation than the lives at stake,” she fumed. Kumar, the operations head, defended his team, citing staff training protocols that included “emergency simulation drills.” Yet, a leaked internal memo revealed only two such sessions in the pod’s three-month lifespan—hardly enough to steel nerves against a real crisis.

The fallout was swift. Southern Skies shuttered operations pending a full inquiry, issuing a mealy-mouthed apology on Instagram: “We regret this isolated incident and are committed to the highest safety standards.” Bookings plummeted 70% overnight, with cancellations pouring in from as far as the UK and UAE. Tourism officials in Kerala, already reeling from a dip in post-monsoon visitors, convened an emergency task force. “This can’t be the headline for Munnar,” declared State Tourism Minister P.A. Mohammed Riyas. Proposals for mandatory third-party audits and real-time telemetry for high-risk attractions are now on the fast track.

Faces of Fortitude: The Human Stories Behind the Headlines

Beyond the mechanics and mishaps, this saga is etched in the faces of those who endured it. For the Safwans, the ordeal has forged an unbreakable bond, tempered in the fire of fear. Back in Kozhikode, they’ve shunned media spotlights, opting instead for quiet therapy sessions and family picnics at sea level. “Heights aren’t for us anymore,” Thoufeena confided to a counselor, her eyes distant. Yet, glimmers of growth emerge: Aisha, once shy, now draws intricate pictures of “flying families,” while Omar’s first full sentence post-rescue was “I brave, Mama.”

Haripriya’s tale adds another layer—a testament to the unsung labor fueling India’s tourism engine. As a single mother supporting her ailing parents, the Sky Dine gig was a godsend, paying double her previous wage at a local dhaba. The incident left her jobless but not defeated. “I’ll find another perch,” she vowed, enrolling in a barista course in Kochi. Her poise during the crisis earned her a commendation from the fire department, a rare honor for “civilian collaborators.”

And then there are the rescuers, the quiet architects of salvation. Praveen Kumar, haunted by a near-miss in a 2022 paragliding rescue, views the event as a call to arms. “Every climb reminds you: Gravity doesn’t discriminate. But neither does courage.” His team, drawn from Kerala’s diverse tapestry—Malayalis, Tamils, and migrants from Bihar—embodies the state’s resilient spirit, honed by annual floods and landslides.

Broader Horizons: Sky Dining’s Double-Edged Sword

This Munnar mishap isn’t an anomaly; it’s a symptom of adventure tourism’s high-wire act. Globally, the sector is stratospheric, projected to hit $1.3 trillion by 2027, per UNWTO estimates. In India, hotspots like Rishikesh’s rafting rapids and Goa’s scuba depths draw 40 million adrenaline junkies yearly. Yet, accidents abound: A 2023 zipline fatality in Himachal Pradesh, a bungee snap in Manali, and now this crane conundrum. Critics argue that profit trumps prudence, with startups chasing viral fame over rigorous vetting.

Proponents counter that regulated risks build character. “Adventure isn’t safe—it’s sanitized danger,” posits Dr. Priya Singh, a Delhi-based risk psychologist. Her research shows that 85% of thrill-seekers report heightened life satisfaction post-experience, crediting the “post-traumatic growth” from brushing mortality. In Kerala, where unemployment hovers at 7%, such ventures create jobs—Southern Skies alone employed 25 locals before the shutdown.

As investigations deepen, calls for reform crescendo. The ATOAI is drafting a “Sky Safety Charter,” mandating annual certifications and AI-monitored hydraulics. Environmentalists, ever vigilant, worry about the ecological footprint: Cranes like Sky Dine’s guzzle diesel, scarring the fragile Ghats biodiversity. “We can’t let tourism tower over nature,” warns the Wildlife Trust of India.

A Lesson Suspended in Time

As the sun sets once more over Munnar’s mist, the Sky Dine crane stands idle—a rusted relic of ambition unchecked. For the Safwan family, it’s a scar that fades but never vanishes, a reminder that the greatest adventures often unfold not in the ascent, but in the uncharted fall. Their story, raw and riveting, urges us to pause amid our pursuits of the extraordinary: How high are we willing to climb, and at what cost?

In the end, survival isn’t just about ropes and rescuers. It’s the unyielding grip of love, the whisper of hope against howling winds, and the profound gratitude for ground beneath our feet. As Safwan reflects, “We didn’t just eat lunch that day. We devoured life itself—and lived to taste it again.”

News

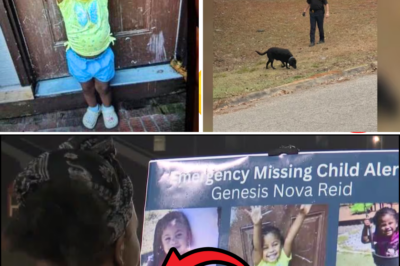

💔 “She Needed the Bathroom,” the Clerk Said — After Pumping Gas and Taking the Key, Genesis and Her Mother Disappeared, Leaving the Car Behind

A small military town in southeast Alabama woke to a nightmare on February 16, 2026, when 33-year-old Adrienne Reid dialed…

🕯️ “She was a beautiful angel” — Loved ones demand answers as Mariah Kletz’s February 7 death inside her own home turns into a murder probe

The quiet suburb of Bloomington, Illinois, shattered under the weight of an unthinkable tragedy in early February 2026. On February…

Heartbroken Grandma Speaks Out After Bloomington Teen Mariah Kletz’s Death Is Investigated as Homicide” 🕯️

The peaceful suburbs of Bloomington, Illinois, have long symbolized the quintessential Midwestern charm: tree-lined streets where children ride bikes freely,…

👨👧👧💬 “I Want the Kids to See More of Dad’s Presence Than Just Mom” — Chilling Words From Caleb Flynn Shock Courtroom After Ashley’s Murder 🖤

The quiet streets of Tipp City, Ohio, a small Midwestern town known for its tree-lined neighborhoods and tight-knit community, were…

🚔 “$1 Million Bond… And a Secret Betting Circle?” — New Motive Surfaces in the Search for Missing Toddler Genesis Reid 🩷🔥

The small town of Enterprise, Alabama, has long been a place where life moves at a measured pace, where neighbors…

😢 “Neighbors Heard Screams in the Night…” — The Chilling Disappearance of 2-Year-Old Genesis Reid Shakes Enterprise 🩷🚨

The quiet streets of Enterprise, Alabama, a small town nestled in the heart of Coffee County, have been transformed into…

End of content

No more pages to load