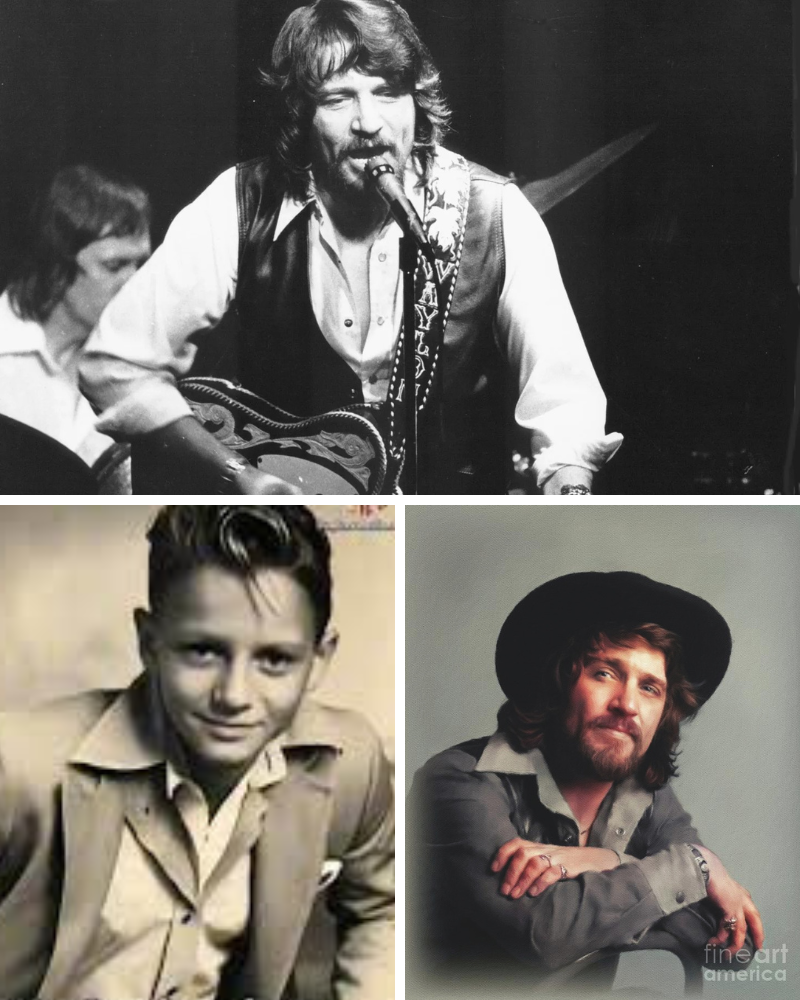

Nashville in the 1960s and ’70s was a machine of sequins and strings, churning out polished anthems under the iron grip of producers who dictated every fiddle scratch and harmony. Enter Waylon Jennings, a lanky Texan with a gravel-throated snarl and a Fender Telecaster slung low like a six-shooter. He didn’t arrive to play nice; he came to torch the rulebook. Born in the dustbowl flats of Littlefield, Texas, on June 15, 1937, Jennings turned country music’s sterile salon into a honky-tonk brawl, birthing the Outlaw movement that injected rock’s raw edge into twang. His story isn’t just one of hits and heartbreak—it’s a gritty chronicle of defiance, excess, and redemption that reshaped an industry and left a legacy echoing from Austin dives to Broadway stages.

Jennings’ path to rebellion started far from Music Row’s glow. Raised in a family of sharecroppers, he picked up the guitar at age 8, mimicking the blues licks crackling from his parents’ radio. By 12, he was spinning records as a DJ on KVOW in Littlefield, sneaking in Little Richard tracks that got him fired for “racial mixing” in a town still clinging to Jim Crow shadows. Undeterred, the high school dropout hitchhiked to Lubbock at 16, landing gigs as a performer and deejay under the alias Jett Williams. It was there, in the rockabilly haze of West Texas, that fate dealt its first wild card: Buddy Holly. In 1958, Holly tapped the 21-year-old Jennings as bassist for his Winter Dance Party Tour. Jennings soaked up the Crickets’ fusion of country, rock, and rhythm, even trading his plane seat to Holly on February 2, 1959—the night “The Day the Music Died” claimed three rock pioneers in a frozen Iowa cornfield. “I gave him my seat, and J.P. Richardson gave me his. Funny how life turns,” Jennings later reflected in his 1996 autobiography Waylon, a no-holds-barred tell-all co-written with Lenny Kaye that laid bare his demons and dreams.

That tragedy could’ve derailed a lesser soul, but Jennings channeled it into fuel. He formed the Waylors, cut rockabilly singles like “Jole Blon,” and rubbed shoulders with Johnny Cash, whose wild-man aura inspired his own freewheeling style. By 1965, a RCA deal lured him to Nashville, but the “Nashville Sound”—Chet Atkins’ syrupy blend of strings and crooners—chafed like a cheap suit. Jennings chafed under producer Don Law’s thumb, churning out tame covers that masked his inner fire. “They wanted me in Nudie suits and smiling for the cameras. I wanted to play what burned in my gut,” he griped in interviews, his long hair and beard a middle finger to the crew cuts and conformity.

The tipping point came in the early ’70s. Jennings had notched modest hits like “Only Daddy That’ll Walk the Line,” but studio battles raged. RCA brass balked at his demands for creative control—picking his own songs, band, and studio—privileges rock acts like the Stones took for granted. “I was fighting for my soul,” Jennings said, tearing up contracts in fits of rage and holing up in RCA’s downtown studios with his ragtag crew, dubbing themselves the Waylors after a misprint on a tour poster. Bootleg tapes of these marathon sessions, later leaked as The Outlaws bootlegs, captured the chaos: amp feedback, whiskey-fueled jams, and Jennings’ Telecaster slicing through the haze like a switchblade.

Enter Willie Nelson, the redheaded renegade who’d fled Nashville for Austin’s cosmic cowboy scene. Their 1971 jam session at Nashville’s Municipal Auditorium—unplugged, unpolished—ignited the spark. “Willie showed up with his guitar, and we just played. No suits, no scripts,” Jennings recalled. What emerged was Outlaw Country: a raw hybrid of Bakersfield honky-tonk, Delta blues, and electric rock, ditching the violins for Tele twang and pedal steel wails. Jennings’ 1973 breakthrough, Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, produced by Tompall Glaser, roared with tracks like the title cut—a rambling anthem of wanderlust—and Honky Tonk Heroes, a tribute to his rodeo roots. Critics hailed it as “the sound of boots on Music Row gravel.”

The revolution hit warp speed in 1976 with Wanted! The Outlaws, a RCA compilation slapping together Jennings, Nelson, Glaser, and Jennings’ wife Jessi Colter. Billed as “Wanted! The Outlaws,” it wasn’t new material but a marketing masterstroke: mug-shot liner notes, rebel rhetoric, and a double-disc dump of renegade cuts. It shattered barriers, selling a million copies in weeks to snag country’s first platinum certification. Hits like “Good Hearted Woman”—a duet with Nelson that snagged CMA Single of the Year—painted the Outlaws as anti-heroes, their longhair rebellion mirroring Vietnam-era unrest. The album’s success forced Nashville to bend: Jennings finally got his reins, helming Ol’ Waylon (1977), country’s first solo platinum LP, fueled by “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love).”

But glory came laced with thorns. The Outlaw tag, once a badge of honor, morphed into a straitjacket. “Don’t You Think This Outlaw Bit’s Done Got Out of Hand?” Jennings growled in a 1978 single, skewering the hype as labels pimped the image for profit. Cocaine-fueled benders and tour-bus blowouts earned him a $2.5 million IRS lien in 1984, nearly bankrupting the empire. Personal scars ran deeper: four marriages, including a stormy union with Colter that birthed hits like “Storms Never Last,” but also custody wars over his six kids. Shooter Jennings, his youngest son with Colter, would later channel that fire into his own psychobilly career, fronting Stargazers and producing tributes to Dad’s rogue spirit.

Television offered a lifeline. From 1979-1985, Jennings narrated The Dukes of Hazzard as the gravelly Balladeer, crooning the theme and popping up in episodes like “Welcome, Waylon Jennings.” It was campy gold, netting him mainstream fans and steady cash amid the chaos. Reunions sweetened the pot: The Highwaymen in 1985 paired him with Nelson, Cash, and Kris Kristofferson for Highwayman, a roots-rock juggernaut that topped charts and toured arenas. “We were the last of the Mohicans—old outlaws riding into the sunset,” Kristofferson quipped.

Health betrayed him in the ’90s. Diabetes ravaged his frame, claiming his left foot in 2001 and forcing him off the road. He quit the blow in ’87 cold turkey—”I woke up one day and said, ‘Enough’”—and channeled sobriety into gospel-tinged albums like Right for the Time (1996). Jennings bowed out on February 13, 2002, at 64, his death from complications mourned by a Nashville he’d once scorned. Over 25,000 fans jammed his funeral at First Baptist Church, where Cash eulogized: “Waylon didn’t follow paths; he blazed ’em.”

The Outlaw flame Jennings lit still crackles. It paved the way for the New Traditionalists of the ’80s—Ricky Skaggs, Dwight Yoakam—and the alt-country wave of the ’90s, from Uncle Tupelo to Wilco. Today’s torchbearers—Sturgill Simpson’s cosmic twang, Chris Stapleton’s soulful grit, even Post Malone’s forays into Waylon covers—owe him a debt. Shooter Jennings keeps the bloodline alive, helming the 2017 tribute Outlaw: Celebrating the Music of Waylon Jennings, featuring Miranda Lambert and Patty Griffin honoring tracks like “I’ve Always Been Crazy.” Books like Michael Streissguth’s Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville (2013) and Brian Fairbanks’ Willie, Waylon, and the Boys (2024) dissect the era, crediting Jennings as the spark that democratized country.

Jennings’ hits—16 No. 1s, from “I’m a Ramblin’ Man” to “Amanda”—weren’t just songs; they were manifestos. “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” skewered the suits, while “Ain’t Livin’ Long Like This” thumbed its nose at mortality. His autobiography, frank as a barroom confession, sold briskly, spawning audiobooks where his voice—worn like boot leather—narrated the highs and hells.

In an industry now flooded with TikTok troubadours and algorithm anthems, Waylon’s ghost looms large. He proved authenticity trumps polish, rebellion births revolutions. As he drawled in Waylon, “I didn’t set out to change the world. I just wanted to play my music.” But change it he did, kicking doors wide for every artist daring to sling low and sing true. Nashville’s smiles got a little grittier, its songs a little bloodier—and for that, the Queen City owes its favorite outlaw a eternal nod.

News

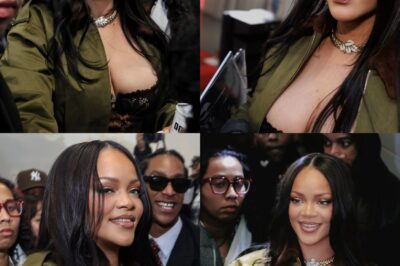

Rihanna Responds to a Fan Saying, “They Saying It’s 2016, Rih”: What Her Viral Reply Really Means

When a fan recently commented, “They saying it’s 2016, Rih,” few expected Rihanna to respond. She often ignores random online…

Rihanna’s Unmatched Face Card: How One Look Became a Cultural Phenomenon

Few celebrities command attention the way Rihanna does. Across red carpets, candid street photographs, and unfiltered social media moments, one…

400,000 FRANCS FOR RELEASE: PROSECUTORS SEEK BAIL FOR OWNERS AFTER DEADLY CRANS-MONTANA NEW YEAR FIRE

Prosecutors in Sion have requested a total of 400,000 Swiss francs in bail to grant provisional freedom to Jacques and…

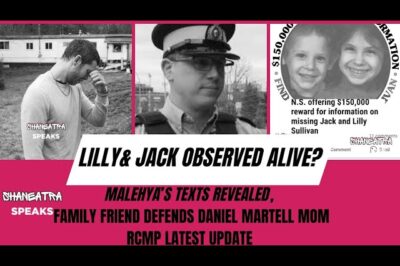

📰 RCMP RELEASES NEW TIMELINE DETAILS IN LILLY AND JACK SULLIVAN CASE AS ALLEGED MESSAGES SPARK FRESH CLAIMS

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has entered another sensitive phase as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police released new…

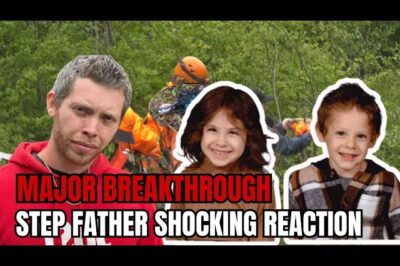

JUST NOW: Investigators Flag Timeline Issues and Re-Examine Key Details in the Disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan

The disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan has taken an unexpected and unsettling turn, according to the latest update released…

A new wave of controversy erupted online this week after the daughter of an NBA legend reportedly came forward with what she described as troubling information involving Stefon Diggs and his relationship with Cardi B.

According to circulating social-media claims, she suggested that Cardi B should reconsider her involvement with the NFL star, citing alleged…

End of content

No more pages to load