🚨 They just pulled something from the river that made seasoned searchers go silent…

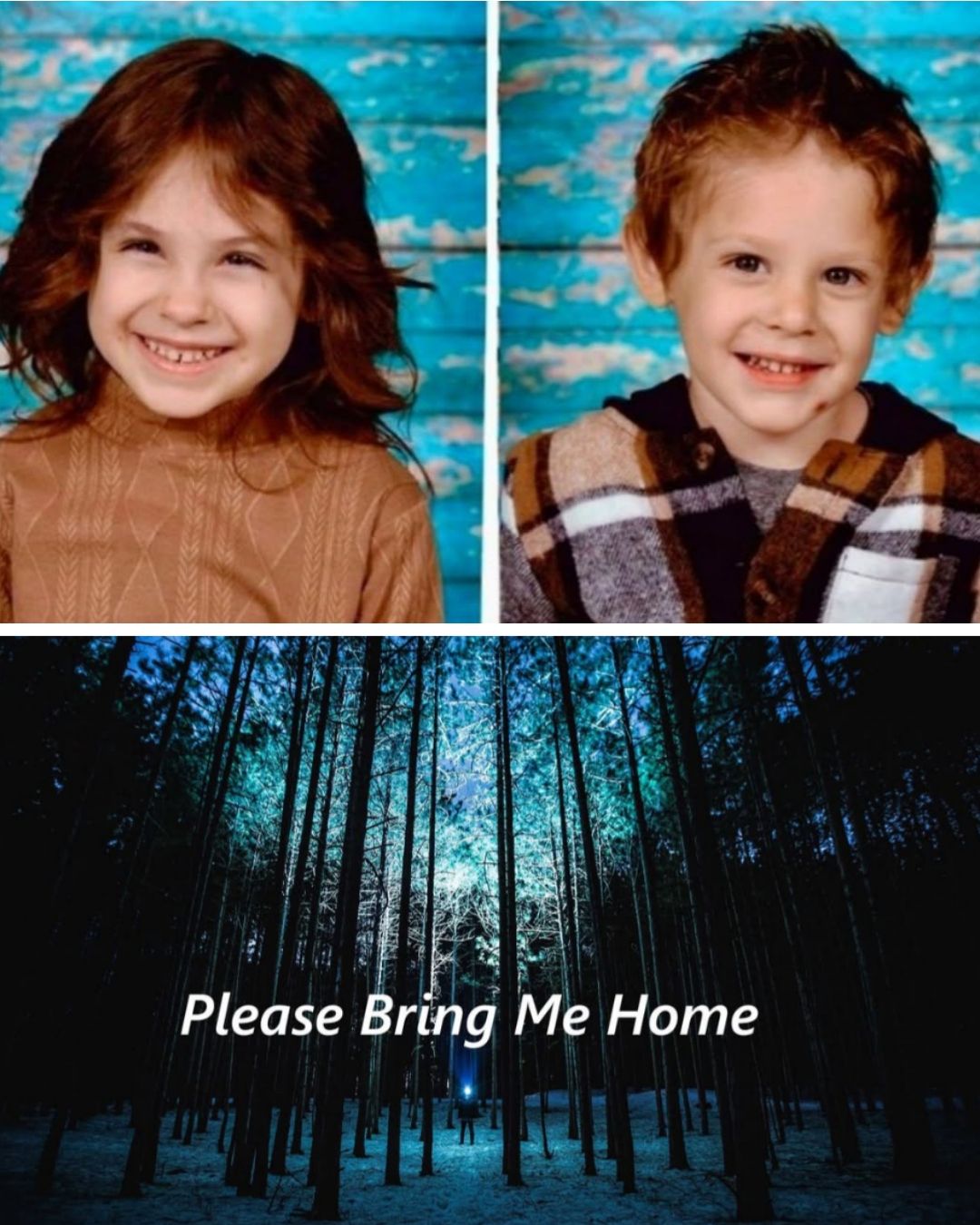

Six months after Lilly (6) and Jack (4) vanished from their Nova Scotia backyard without a single scream, 30 volunteers spent all weekend wading through ice-cold water in a final desperate push before winter seals everything shut.

They found children’s clothing. A blanket. A tricycle half-buried in the mud. And one item so disturbing that even the cops won’t say what it is yet.

One volunteer whispered: “If that belongs to one of the kids… this case just flipped upside down.”

RCMP already swooped in and declared everything “not relevant” — but why the rush to shut it down? What exactly did they bag and tag before anyone could take a closer look?

The family is breaking. The theories are exploding. And Canada can’t look away.

You need to see what they discovered. Full story + photos that will haunt you → click below.

River Yields Chilling Clues in Six-Month Nightmare Search for Missing Canadian Siblings

LANSDOWNE STATION, Nova Scotia — The Middle River was running fast and cold last Saturday when the volunteers finally reached the stretch no one wanted to search again.

Thirty exhausted men and women from the group Please Bring Me Home fanned out along 18 miles of tangled riverbank, boots sinking in mud, hands numb, faces whipped raw by November wind. They had one weekend — maybe the last before snow buries everything for six months — to find Lilly and Jack Sullivan, ages 6 and 4, who disappeared from their rural backyard on May 2 without a trace, a scream, or a single footprint.

By sundown, they had something. Actually, they had several somethings. And whatever one of those items was, it stopped seasoned searchers dead in their tracks.

Sources on the ground told reporters that the discoveries included a child-sized T-shirt snagged high on a root wad, a child’s blanket weighted down with river stones, a rusted tricycle too small for any neighborhood kid still riding today, and one sealed evidence bag that volunteers were ordered not to discuss. RCMP officers arrived within minutes of that final find, took possession, and within hours declared every single item “not related to the investigation.”

That swift dismissal only poured gasoline on the speculation fire that’s been burning across Nova Scotia for half a year.

The search was billed as a last-ditch private effort after the Royal Canadian Mounted Police scaled back active operations in August. The Ontario-based nonprofit, known for cracking cold cases police had abandoned, raised money overnight, drove eight hours, and hit the water at dawn. They used drones, side-scan sonar, and good old-fashioned grid lines — the same methods that recovered 50 missing persons in other files.

What they pulled out wasn’t supposed to be there.

The T-shirt was faded pink — close, but not an exact match to the one Lilly wore in the last known photo. The blanket carried no tags, no monograms, nothing obvious. The tricycle’s seat was cracked and sun-bleached, but the handlebar streamers were still knotted in the same double-loop style the kids’ grandmother swears Lilly loved.

Then came the item no one will name. Two volunteers independently described a reaction among the RCMP evidence techs that one called “the kind you only see at a homicide scene.” Whatever it was, it went straight into a locked van and was driven away under escort.

By Monday morning, the official line was locked tight: “No items recovered are believed to be connected to the disappearance of Lilly and Jack Sullivan.” Case closed — at least as far as the public is concerned.

That’s not sitting well with the family or the army of online sleuths who have turned this into Canada’s most watched missing-children case since the Skelm family vanished in Cape Breton twenty years ago.

Lilly and Jack were supposed to be safe. Their home on Gairloch Road sits in a quiet clearing ringed by steep ravines and thick forest. Mom Malehya Brooks-Murray was in the bedroom with their baby sister. Stepfather Daniel Martell was steps away. Lilly poked her head in at 10 a.m. to ask for juice. Minutes later — silence. No doors slammed. No car engines. No strangers reported for miles.

The 911 call came at 10:01 a.m. By noon, half the province was on alert.

The first 48 hours were chaos in the best possible way: helicopters, dogs, divers, thermal drones, hundreds of volunteers. Searchers found bear cubs, deer, even a lost hiker — but no children. The Middle River was running high from spring melt; theories centered on a tragic slip and drowning. Except no bodies surfaced when water levels dropped in July. No clothing. No shoes. Nothing.

That’s when the narrative started to crack.

Tips flooded in — 860 and counting. A tan sedan seen near the house. A man and woman with two small children at a New Brunswick gas station. A screaming child heard in the woods minutes after the 911 call — drowned out by the very helicopter sent to save them. Every lead went cold.

Polygraphs were administered to the parents and stepfather. Results: inconclusive but no deception detected. The biological father, Cody Sullivan, who hadn’t seen the kids in years, was raided at 4 a.m., questioned for days, and cleared. The $150,000 reward still sits unclaimed.

Six months in, the official search became a monitoring operation. That’s when Please Bring Me Home stepped in.

Founder Nick Oldrieve, a grizzled ex-cop who’s pulled more bodies out of water than he’ll ever admit, told reporters before the weekend push: “Rivers lie. They hide things for months, then cough them up when the flow changes. We’ve seen it a hundred times.”

They saw it again Saturday.

Whether those items will ever be made public remains to be seen. The RCMP has sealed the evidence logs, citing the ongoing nature of the investigation. Family members were shown photographs Sunday night and asked for identification. Sources say the children’s mother collapsed when shown one image; another family member stormed out refusing to believe the official “not connected” line.

As of Sunday evening, Please Bring Me Home packed up their gear and vowed to return in spring with cadaver dogs trained specifically for water recoveries. Oldrieve’s parting words to the cameras: “We didn’t find Lilly and Jack this weekend. But the river just told us it’s still holding secrets.”

Back in Lansdowne Station, the posters are fading on telephone poles. The Facebook groups are closing in on 100,000 members. And every time the wind rattles the trees behind the Sullivan house, someone swears they hear a child laughing — or crying.

The case remains classified as missing persons, not criminal. For now.

But after last weekend, a lot of people aren’t so sure anymore.

News

Man Sentenced to Life for Murder of Girlfriend in East Kilbride Flat – Case Highlights Hidden Struggles in Relationships

She called him her “soulmate”… but one night, everything changed forever. 💔 Phoenix Spencer-Horn, 21, came home after work feeling…

Former Judge on NewsNation: Murder Charge Against Dr. Michael McKee ‘Only the Beginning’ as Evidence Mounts in Ohio Double Homicide

BREAKING: Former Judge Tarlika Nunez-Navarro just dropped bombshells on NewsNation about the double murder charges against Dr. Michael McKee. 😱⚖️…

Illinois Surgeon Waives Extradition After First Court Appearance in Double Murder Case Tied to Ex-Wife and Ohio Dentist Husband

A respected vascular surgeon in his first court appearance… and he just waived extradition. 😱⚖️ Dr. Michael McKee, 39, stood…

‘She Is My Everything’: Mother’s Emotional Breakdown as Items Near Scene Fuel Questions in Camila Mendoza Olmos Case

“She is my everything…” 💔😭 Camila Mendoza Olmos’ mother broke down in tears, repeating those words through sobs after investigators…

Parents’ Heartbreaking Denial as Body Identified as Missing Texas Teen Camila Mendoza Olmos; Shoes at Scene Add to Lingering Questions

“That’s not my daughter…” 😢💔 The parents of 19-year-old Camila Mendoza Olmos collapsed in tears as they tried to identify…

Mystery Persists a Decade Later: Tiffany Valiante’s Death Ruled Suicide, But Family Alleges Hate-Crime Murder in New Lawsuit

She left home fully dressed at 9:00 p.m… smiling, alive. By 11:16 p.m., she was dead on train tracks 4…

End of content

No more pages to load