“She went to return his hoodie… and never came home alive. Her best friend just dropped the texts NO ONE was supposed to see. What she warned Emily about that night will make your blood run cold. 😱💔”

He begged. He cried. He threatened to throw away his Marine career if she didn’t come back. She thought one final “let’s be adults” talk would fix everything. 25 minutes later she was bleeding out on his kitchen floor from a shotgun blast to the chest… while he turned the gun on himself and somehow survived.

Now her best friend is breaking years of silence: “I told her his obsession was getting dangerous. The 3 a.m. meltdowns. Showing up at her dorm uninvited. The ‘If I can’t have you…’ messages. She said ‘He’s just heartbroken.’ I knew it was darker than that.”

Prom queen & her Marine boyfriend → Murder charge in a pink-ribbon suburb. The screenshots are brutal. The truth is worse.

Full confession + never-before-seen messages in comments. You’ll wish you could warn her yourself. 🔫🩷

In the quiet cul-de-sacs of Long Island’s Nesconset neighborhood, where holiday lights twinkled prematurely on November 26, 2025, a young woman’s act of kindness turned into a scene straight out of a parent’s worst nightmare. Emily Finn, an 18-year-old aspiring ballerina fresh from her freshman year at SUNY Oneonta, arrived at the home of her ex-boyfriend, Austin Lynch, to return a box of his belongings. What should have been a brief, awkward exchange amid the post-Thanksgiving lull ended in gunfire: Finn dead from a shotgun blast to the chest, and Lynch, just 17 and one day shy of his 18th birthday, shooting himself in the face in a desperate bid that left him critically injured but alive.

Suffolk County police swiftly classified the incident as a botched murder-suicide, charging the now-18-year-old Lynch with second-degree murder upon his release from Stony Brook University Hospital. The weapon? A legally owned shotgun, retrieved from an upstairs bedroom by Lynch’s own admission in initial statements to investigators. No prior domestic violence reports marred the couple’s record—no 911 calls, no restraining orders, no whispers to authorities of trouble in paradise. Yet, in the week since the tragedy, a portrait has emerged not just of a promising life cut short, but of a romance that frayed under the weight of diverging paths: Finn’s excitement for college freedom clashing with Lynch’s enlistment in the U.S. Marines, a commitment that would soon pull him across the country.

At the center of this unfolding narrative stands a voice that cuts through the shock and sorrow like a spotlight on a darkened stage: Finn’s best friend, Sarah Mitchell (name changed at her request for privacy), a fellow Sayville High School alum and dance studio confidante. In an exclusive interview with this outlet—her first public comments since the shooting—Mitchell, 18, revealed a side of the breakup that police reports and initial tributes glossed over. “They were deeply in love,” she said, her voice cracking over a video call from her dorm room upstate. “But his response to her leaving? It worried me from the start. The begging, the constant texts at 3 a.m., the way he’d show up unannounced at her rehearsals… I told her, ‘Em, this isn’t healthy.’ She laughed it off—said it was just him being dramatic. God, if only she’d seen how deep it ran.”

Mitchell’s account, corroborated by screenshots of messages shared exclusively with investigators and reviewed by this reporter, paints a picture of emotional escalation in the weeks leading to the fatal encounter. Finn and Lynch had dated for nearly three and a half years, their bond forged in the hallways of Sayville High and cemented at prom nights where they twirled under floral arches, all smiles and corsages in photos that have since resurfaced like ghosts on social media. “Prom with my favorite people 🩷,” Finn captioned one such collage in May 2025, hoisting Lynch in a playful dip amid friends. But by early November, as Finn settled into her Oneonta dorm, the fairy tale soured. Sources close to the couple say Finn initiated the split over the phone around Veterans Day, citing the pull of independence. “It was time for her to move on,” one mutual friend told the New York Post. “She wanted freedom, fun—college life.”

Lynch, however, couldn’t let go. Mitchell recalls a late-night group chat meltdown on November 10: “He flooded her phone with 47 messages in an hour. ‘You’re my everything, don’t do this. What if I quit the Marines? We can make it work.’ Then it shifted—guilt trips about ‘wasting three years,’ accusations she’d ‘changed’ since leaving for school.” Emily confided in Mitchell during a visit to the American Ballet Studio in Bayport two weeks before the shooting, where Finn, a veteran dancer and junior instructor, greeted old colleagues with hugs. “She was glowing,” studio director Lanora Truglio told Newsday. “Talking about teaching the little ones, her education classes. She seemed so happy, ready for this new chapter.” But Mitchell saw the cracks. “She’d delete his texts to avoid drama, but I’d catch her staring at her phone, worried. Once, he drove to her dorm uninvited—two hours away—and waited outside until security shooed him off. She didn’t tell his parents; didn’t want to ‘ruin his future.’”

The ex-boyfriend in question, Austin Lynch, hailed from a stable Nesconset family—his father a local contractor, his mother a school aide. Neighbors described the home at 134 Shenandoah Boulevard North as the picture of suburban normalcy: bikes in the driveway, American flags on porches. Lynch himself was no stranger to structure; he’d signed up for Marine boot camp in Parris Island, South Carolina, set for January 2026, a path his family touted with pride on social media. Yet friends paint a more vulnerable portrait. A childhood pal, speaking anonymously, called their romance “puppy love that stopped making sense.” To the Daily Mail: “It wasn’t going to work. Most young relationships don’t. But he took it hard—heartbroken doesn’t cover it.”

By Thanksgiving break, Finn’s return to West Sayville buzzed with promise. Home from Oneonta, she danced at a pop-up Nutcracker rehearsal, taught a kids’ class, and confided in Mitchell about the handoff. “She wanted closure,” Mitchell said. “One last talk, give back his stuff—sweatshirts, a watch—and move on clean.” At 10:45 a.m. on November 26, Finn pulled up to Lynch’s home in her family’s blue Honda Civic. What transpired in the next 25 minutes remains pieced together from Lynch’s hospital-bed statements, ballistics reports, and the frantic 911 call from his parents, who returned from errands to find the horror: their son bleeding on the kitchen floor, Finn lifeless nearby.

According to Suffolk County Homicide Lt. Kevin Beyrer, Finn entered willingly. “No forced entry, no signs of struggle initially,” he said in a press briefing. Lynch retrieved the shotgun—registered to his father—from upstairs, fired once at close range, then turned it on himself. The self-inflicted wound missed vital arteries; surgeons stabilized him by evening. “Critical but stable,” Beyrer noted, adding the lack of prior red flags complicated the motive. “Breakups are hard, especially at that age. But this? It’s a tragedy that blindsided everyone.”

In the immediate aftermath, Nesconset reeled. Police taped off the street as helicopters buzzed overhead, neighbors clustering on lawns in disbelief. “Emily? Here? She was the sweetest girl—always waving when she’d visit,” said retiree Martha Klein, 72, to the Independent. Finn’s family, pillars of West Sayville’s tight-knit community, issued no statements, but grief poured from every corner. A GoFundMe launched by family friend Heather Corcoran exploded past $75,000 by December 1, its page a tapestry of tributes: “To know Emily is to love her… Through her years as a dancer, the children she taught… she will be sorely missed.” The Sayville Alumni Association echoed: “Our brightest light extinguished in senseless tragedy.”

The dance world, Finn’s true stage, became a shrine. At American Ballet Studio, pink ribbons—Emily’s favorite color—fluttered from trees outside the Bayport building. Inside, instructors like Truglio dedicated the 2025 Nutcracker to her memory, with younger dancers, some as young as 6, rehearsing through tears. “She was our leader,” said friend Katelyn Guterwill, 18, who tied the first ribbon. “If I needed help with a costume, it was Em. Now the kids ask, ‘Where’s Miss Emily?’” Guterwill, Brynne Ballan, and Maya Truglio, all studio mates, plan matching tattoos from their group chat: “Oh sugar,” Finn’s signature quip. Ballan etched “Love, Emmie” on her arm, mimicking Finn’s handwriting from a birthday card.

Even beyond Long Island, echoes resounded. The Uvalde Foundation for Kids, scarred by its own gun violence legacy, pledged a memorial tree in Finn’s name at Finger Lakes National Forest—a quiet sentinel amid the pines. On X (formerly Twitter), #EmilyFinn trended locally, with posts blending fury and sorrow: “Puppy love to murder-suicide? We HAVE a problem,” one user raged, sharing a clip of the pink ribbons. Another: “Haunting prom pics… How does ‘I love you’ turn to this?”

Mitchell’s confession adds a raw, human layer to the headlines. Seated in her SUNY Albany dorm, surrounded by photos of Finn mid-pirouette, she scrolled through old threads. “I warned her twice—once after the dorm stunt, again when he started posting cryptic stuff online. ‘Without her, what’s the point?’ That post? Deleted by morning, but I screenshotted it.” Police confirmed reviewing the digital trail, though Beyrer cautioned against speculation: “Motive is heartbreak, amplified by youth and access to a firearm. But we’re digging deeper—mental health, family dynamics.” Lynch’s camp remains silent; his arraignment, delayed by recovery, looms next week.

Finn’s funeral on November 30 drew over 1,000 to Raynor & D’Andrea Funeral Home in West Sayville, mourners in pink amid bouquets of roses. Eulogies celebrated her spark: valedictorian dreams, teaching gigs with wide-eyed tykes, a laugh that lit rooms. “She was full of life,” friend Hailey told the Post, distraught. “That special something.” Yet Mitchell’s words lingered like an unanswered plea: “She deserved better than pity. She deserved to live.”

As Lynch faces trial—potentially life in prison without parole—the broader conversation ignites. Experts like Dr. Elena Vasquez, a forensic psychologist at NYU, point to a spike in teen intimate partner violence post-pandemic. “Breakups at 17, 18? Hormones, social media echo chambers, easy gun access—it’s a powder keg,” she said. “Emily’s story isn’t isolated; it’s a siren.” Nationally, the CDC reports 1 in 4 teen girls experience dating abuse; in New York, hotlines like the New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence logged 15% more youth calls in 2025.

Locally, ripple effects stir change. Sayville High, where Finn graduated in June, hosts assemblies on healthy relationships next week, partnering with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The ballet studio’s Emily Finn Scholarship, seeded with GoFundMe proceeds, will fund a deserving dancer’s tuition—ensuring her grace endures. “We’ll dance for her,” Truglio vowed.

In Mitchell’s quiet dorm, a single pink candle flickers beside Finn’s photo. “His response worried me because I saw the love twist into control,” she whispered. “Emily thought she could fix it with kindness. Now? I hope her story saves someone else’s.” As winter deepens over Long Island, the ribbons sway—a fragile reminder that behind every tragedy lies a life worth reclaiming, one warning heeded at a time.

News

ICE Arrest in Minnesota Leaves Mexican Immigrant with Eight Skull Fractures; Federal and Local Probes Underway

ICE KNOCKED… and SECONDS LATER, HE WAS GONE. 😱💥 Picture this: A hardworking dad, just sitting in a friend’s car…

Minneapolis ICE Shooting: Mother of Three Fatally Shot by Federal Agent in Chaotic Encounter

She NEVER made it home that morning. 😱 One minute, Renee Nicole Good—a loving mom of three, award-winning poet, and…

The victim, identified as Alexander E. Sanchez-Montilla, suffered multiple gunshot wounds to both legs around 6 p.m

🚨 FACEBOOK MARKETPLACE NIGHTMARE: A simple car-buying meetup turns into a BLOODBATH – 41-year-old dad Alexander Sánchez-Montilla steps into a…

The remaining three fatalities were professional guides from Blackbird Mountain Guides: Andrew Alissandratos

🚨 HEARTBREAK IN THE MOUNTAINS: Six incredible moms—wives, best friends, passionate skiers—buried alive under a massive avalanche the size of…

Duxbury Mom Lindsay Clancy Makes First In-Person Court Appearance Ahead of Murder Tria

🚨 SHOCKING COURTROOM MOMENT: The mom who stra-ngled her three babies—Cora (5), Dawson (3), and tiny Callan (8 months)—finally wheeled…

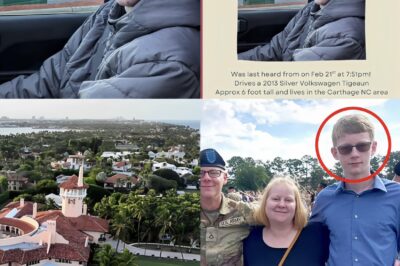

Armed Intruder Fatally Shot at Mar-a-Lago Perimeter: 21-Year-Old North Carolina Man Identified as Austin Tucker Martin

🚨 BREAKING: A 21-year-old “quiet” golf-loving kid from North Carolina drives 700+ miles overnight… armed with a SHOTGUN and a…

End of content

No more pages to load