🧸 WOOLLY WHISPERS: Born with a golden mane that cloaked her like a fairy-tale curse, Minnesota’s tiniest sideshow star stole hearts… but at what price? Alice Doherty’s silky shroud hid a soul craving normalcy—until one quiet retirement couldn’t silence the stares. What if her “miracle” fur was the family’s fortune… and her forever cage? 😔

From toddler tours to teen tragedies… the golden-haired lass who lit up dime museums now haunts with her hidden heartache. Dare to peek behind the poster? Unravel the fur that fate forgot. 🌟

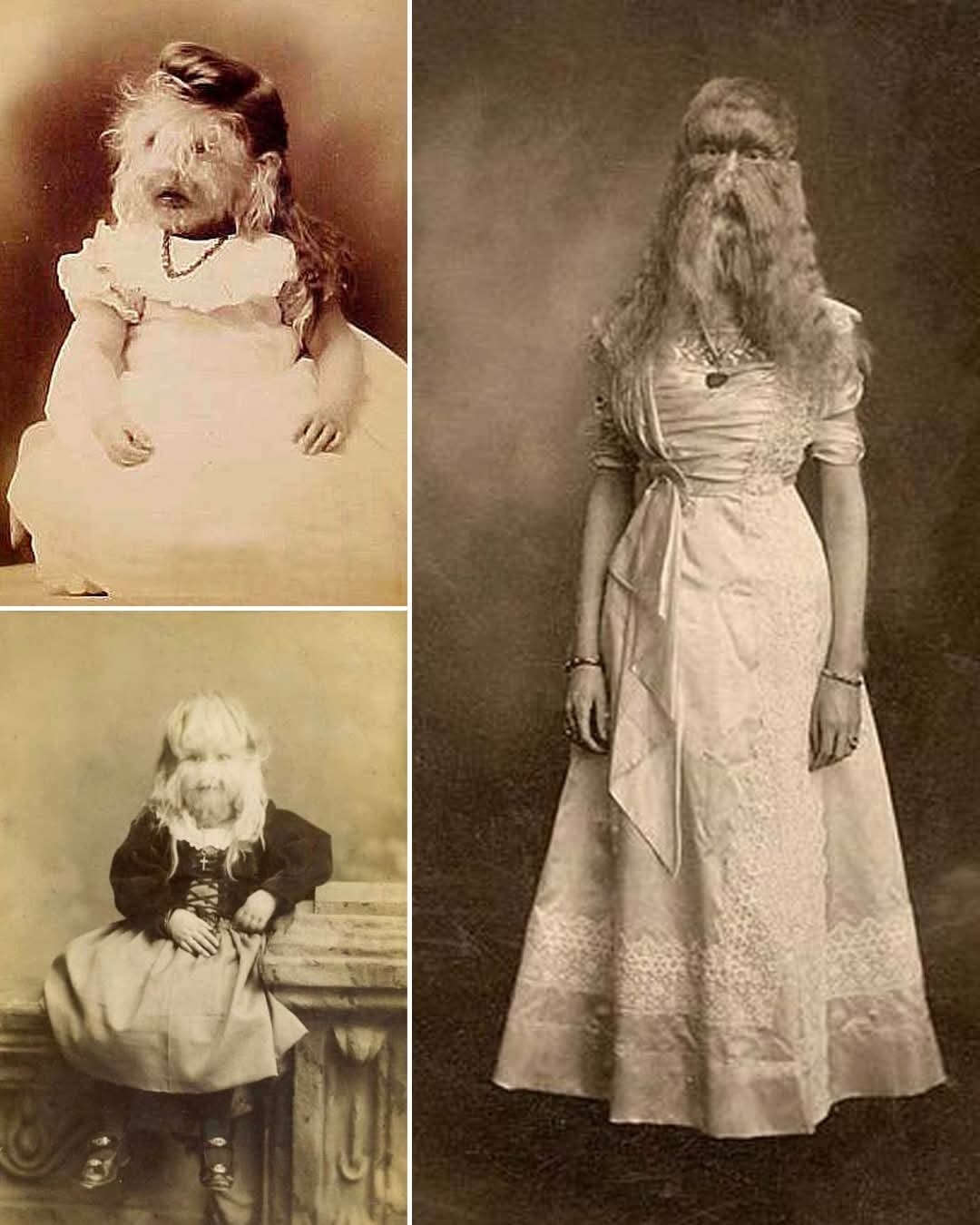

In the frost-kissed cradle of late-19th-century Minneapolis, where the Mississippi’s murmur mingled with the hum of nascent industry, a child emerged into the world not with a cry, but with a cascade of controversy. On March 14, 1887, Alice Elizabeth Doherty entered life covered head to toe in a luxurious mantle of fine, silky blonde hair—two inches thick at birth, shimmering like spun gold under the gas lamps of her parents’ modest home. Dubbed the “Minnesota Woolly Girl” by awestruck exhibitors, Alice bore the exceedingly rare affliction of hypertrichosis lanuginosa, a genetic anomaly afflicting perhaps one in a billion, turning her into a living curiosity that would propel her family from genteel poverty to sideshow stardom. Yet beneath the billboards and the gasps of dime-museum crowds lay a tragedy etched in endurance: A bright, bookish girl paraded as a “freak of nature,” her golden locks a ticket to fortune but a chain to isolation, culminating in a retirement shadowed by health woes and the unyielding weight of a lifetime on display. Alice’s story, pieced from faded cabinet cards, family ledgers, and the yellowed clippings of Midwest matinees, isn’t merely a footnote in the annals of American oddities—it’s a poignant parable of exploitation’s glittering veneer, where wonder warred with wistfulness in an era that commodified the congenital.

The Dohertys—William Edward Doherty, a day-laboring Irish immigrant with a blacksmith’s brawn, and his wife Mary, a seamstress of Scottish stock—were ordinary Minnesotans, their brood including a son, William Jr., and daughter Minnie, both untouched by Alice’s anomaly. The couple’s first glimpse of their third child in a Hennepin County birthing room must have been a tableau of terror and temptation: Alice, robust at 7 pounds 8 ounces, her diminutive frame (barely 18 inches) enveloped in a pelt that evoked ancient myths—the Ambras Syndrome sufferers of Renaissance courts, or the “dog-faced boy” Fedor Jeftichew who thrilled P.T. Barnum’s tents. Hypertrichosis lanuginosa, as physicians later diagnosed (consulting texts from Vienna’s medical archives), stems from a dominant gene mutation triggering fetal vellus hair to persist and proliferate unchecked—lanugo that blankets the body like a newborn’s down, but in Alice’s case, evolving into a lustrous coat of 7-to-13-inch strands by adolescence, soft as cashmere yet suffocating in Minnesota’s sweltering summers. “A miracle or a monster?” Mary reportedly wept to a family physician, Dr. Elias Hawthorne, whose 1888 case study in the Minnesota Medical Monthly—one of the earliest U.S. publications on the condition—painted Alice as “a sylvan sprite, her auric aura a divine deviation.” Far from a medical marvel, though, Alice’s arrival coincided with the Gilded Age’s grotesque gold rush: The post-Civil War freak show boom, fueled by Barnum’s bombast and dime-novel dime-store sensationalism, where “human curiosities” fetched fortunes amid economic churn.

By age two, the Dohertys—strapped by William’s intermittent forge work amid the Panic of 1893—had pivoted to promotion. Alice’s debut came in a rented storefront on Minneapolis’s Nicollet Avenue, a “penny palace” where locals gawked for a nickel at the “Woolly Baby from the North Woods.” Billed initially as “A.J. Jr.,” a coy nod to her initials, she sat placidly in a high-backed wicker throne, her golden fringe parted to reveal cherubic cheeks and eyes “blue as Lake Superior,” per a St. Paul Pioneer Press puff piece that drew 500 spectators in a weekend. Demand swelled like the spring thaw: By 1890, the family toured the Midwest circuit—St. Louis fairs, Chicago’s Columbian Exposition sideshows—renting velvet-draped booths where Alice recited nursery rhymes or plucked a toy harp, her voice a tinkling counterpoint to the crowd’s coos. “The most miraculous mite ever minted,” gushed a Wisconsin scribe in 1892, while a Michigan matron marveled at her “frolicsome felinity—like a kitten in kid gloves.” Earnings escalated: Local gigs netted $50 weekly (a foreman’s wage), ballooning to $200 on tour—enough for the Dohertys to shutter William’s anvil and buy a Queen Anne rowhouse in South Minneapolis, complete with a backyard aviary for Alice’s pet canaries, her sole companions amid the clamor.

Yet the spectacle’s shine masked a somber subtext. Alice, by all accounts a prodigy of poise—devouring Dickens at seven, fluent in French from tutor-travels—was no eager exhibitionist. Family lore, gleaned from Minnie’s 1942 oral history archived at the Minnesota Historical Society, paints a portrait of private protest: “She’d beg for books over bows, curling into corners with Little Women while Mother manicured her mane.” Hypertrichosis, benign in vitality (no organ impairment, unlike its congenital kin), exacted epidermal exactions: The pelt trapped heat like a fur coat in July, prompting summer soaks in iced oatmeal baths; winters brought chafing cracks, slathered in lanolin from her own sheared clippings (a macabre memento sold as “Woolly Relics” for a dime). Socially, it was a solitary siege: Peers shunned the “wild child,” her homeschooling a haven of Hawthorne novels and harp lessons, while suitors? A non-starter in an era where eugenics tracts decried “defectives” as Darwinian dead-ends. “I am no beast of burden,” Alice confided to a carnival confessor in 1905, her words inked anonymously in The Sideshow World gazette— a rare rebellion against the routine: 10-minute “shows” thrice daily, her script a singsong of “See my silken shroud, spun by stars above!”

The zenith—and nadir—unfolded in the 1900s’ touring heyday. By 1905, at 18, Alice’s auric armor spanned 9 inches on her cheeks, a “golden glory” that commanded $500-per-week contracts with the Sells-Floto Circus, barnstorming from Duluth to Denver. Posters proclaimed her “The Living Golden Fleece,” flanked by faux Grecian urns and lyres, her act augmented by a “hair-harvest” demo—snipping a lock for souvenirs, the snip synchronized to Strauss waltzes. Contemporaries abounded: The “Alligator Boy” Ollie Edwards toured tandem in 1908, their “Furry Friends” double-bill drawing 10,000 in St. Louis alone. Yet glut bred grit: Alice chafed at the “glut of glabrous grotesques,” as a 1910 Variety vignette vented, her earnings earmarked for siblings’ schooling—Minnie to nursing college, William Jr. to law—while she scrimped on salves. Health harbingers hovered: Chronic bronchitis from booth-bound drafts, exacerbated by the pelt’s “lung-lining” itch, foreshadowed frailty. A 1912 Chicago World’s Fair stint—her swan-song spectacle—netted $2,000 but wrung exhaustion; Alice fainted mid-monologue, her collapse chalked to “over-enthusiasm” in press releases, but Minnie’s memoir murmurs “malaise of the masked.”

Retirement rippled in 1915, at 28—a rarity in the “freak” fray, where many like Lionel the Lion-Faced Man labored till the grave. Flush with $20,000 in savings (a lumber baron’s bounty), the Dohertys decamped to a Dallas bungalow, Alice’s “exile of ease” funded by frugal investments in Texas oil scrip. She shed the spotlight for solitude: A private library stocked with Austen and Audubon, a menagerie of macaws mirroring her mane’s hue, and occasional cameos at charity galas—reading Poe to orphans, her voice a velvet veil over veiled vanity. Suitors surfaced sporadically: A 1920s oilman proposed via proxy, rebuffed with “My heart’s my own, unshared with hides”; friendships flowered with fellow “curios” like Ella Ewing, the 8-foot-4 giantess, their epistles archived at the Harry Ransom Center. Yet the yoke lingered: Hypertrichosis’s hormonal havoc—unmedicated in pre-endocrinology days—stoked skin sensitivities and seasonal sloughs, her golden glory graying to silver by 40, a “weary web” she whimsically wove into wall-hangings.

Tragedy tiptoed in the 1930s’ dustbowl doldrums. Bronchial pneumonia—aggravated by Dallas’s damp damps and her pelt’s perpetual prison—struck in spring 1933, a respiratory ravager that felled 100,000 Americans amid the Great Depression’s frail fringes. Confined to her canopied bed, Alice dictated a final flourish to Minnie: “I was woolly, not wild—wonder wrapped in whimsy.” She slipped away June 13, 1933, at 46, her passing parsed in the Dallas Morning News as “The Woolly Wonder Winds Down,” a paean to her “philanthropic phantom.” No grand obsequies—just a quiet Catholic rite at Calvary Hill Cemetery, her grave a modest mound under a mulberry tree, headstone etched “Alice E. Doherty, Beloved Sister, 1887-1933.” Assets apportioned: $15,000 to family, $5,000 to Minneapolis charities for “children of curiosity.” Mary’s 1941 demise dredged diaries detailing doubts—”We paraded our pearl for pennies; forgive the folly”—while William’s 1935 stroke silenced secrets.

Alice’s afterlife aches with ambiguity. Hypertrichosis, once a “freak flag,” now flags genetic frontiers: Modern lasers (YAG and diode) depilate with 90% efficacy, per 2024 Journal of Dermatological Treatment trials, sparing successors like Thailand’s “Supatra Sasuphan,” the 2010 Guinness “hairiest girl” who attends school sans spectacle. Her artifacts—cabinet cards at the Minnesota History Center, a 1905 lock at the Smithsonian’s freakery file—fuel fascination: A 2022 Reddit resurrection r/Damnthatsinteresting amassed 11K upvotes, users unearthing “Alice’s agency” amid “animalized” ads. Documentaries like Woolly Wonders (2021, PBS) probe the pathos, interviewing descendants who decry “dime-store Darwinism,” while TikTok’s #WoollyGirl revives her rhymes, 5M views blending empathy with emoji. Critics contextualize: As disability studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson notes in Staring (2009), Alice embodied “the extraordinary body as economic engine,” her exploitation a Gilded echo in today’s influencer ills. Ethically, it’s a tightrope: Consent coerced by circumstance, her “yes” a youthful yoke.

In Minneapolis’s millennial glow, Alice’s legacy lulls like a lullaby lost. A 2019 historical marker at her birthsite—unveiled by the Hypertrichosis Awareness Network—reads: “Here bloomed the Woolly Girl, a golden thread in humanity’s tapestry.” No statues, no spectacles—just scholarships for “scholars of the singular,” funded by her frugal fortune’s fruits. Minnie’s nieces, now nonagenarians in St. Paul, share sepia smiles: “Auntie Alice abhorred audiences, adored avians—her cage was cash, her key compassion.” In an Instagram age of augmented auras, her tale tempers trends: Beauty’s not bald; it’s bravely borne. The Minnesota Woolly Girl didn’t dazzle to deceive—she endured to enlighten, her golden grief a gossamer gift from history’s hushed heart.

News

The victim, identified as Alexander E. Sanchez-Montilla, suffered multiple gunshot wounds to both legs around 6 p.m

🚨 FACEBOOK MARKETPLACE NIGHTMARE: A simple car-buying meetup turns into a BLOODBATH – 41-year-old dad Alexander Sánchez-Montilla steps into a…

The remaining three fatalities were professional guides from Blackbird Mountain Guides: Andrew Alissandratos

🚨 HEARTBREAK IN THE MOUNTAINS: Six incredible moms—wives, best friends, passionate skiers—buried alive under a massive avalanche the size of…

Duxbury Mom Lindsay Clancy Makes First In-Person Court Appearance Ahead of Murder Tria

🚨 SHOCKING COURTROOM MOMENT: The mom who stra-ngled her three babies—Cora (5), Dawson (3), and tiny Callan (8 months)—finally wheeled…

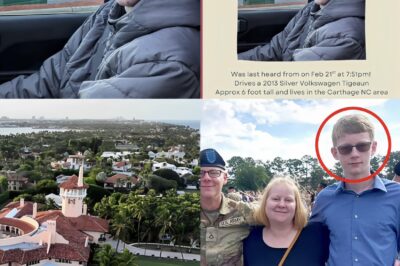

Armed Intruder Fatally Shot at Mar-a-Lago Perimeter: 21-Year-Old North Carolina Man Identified as Austin Tucker Martin

🚨 BREAKING: A 21-year-old “quiet” golf-loving kid from North Carolina drives 700+ miles overnight… armed with a SHOTGUN and a…

Tragedy in Ocala: U.S. Coast Guard Veteran and Family of Four Found Dead in Suspected Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

🚨 IMAGINE THIS: He calls his mom that afternoon, laughing, planning dinner… “See you soon, Ma.” THAT NIGHT, silence. A…

The disappearance of 36-year-old Shana M. Umbreit from this small Lake Huron community has ended in tragedy

A small-town Michigan mom vanishes after a late-night gas station stop. Three weeks later, her body turns up in a…

End of content

No more pages to load