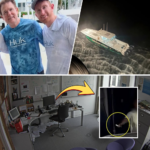

Outrage is sweeping across France’s northern coastline amid shocking revelations about how authorities are handling the ongoing migrant crisis in the English Channel. Reports indicate that French officials have been distributing life jackets to people attempting small boat crossings to the UK. These life-saving devices, provided to ensure safer passages amid dangerous conditions and overcrowded dinghies, are sparking intense backlash from critics who see it as indirect facilitation of illegal migration rather than prevention.

The practice stems from a humanitarian angle: many smugglers supply substandard or no flotation gear, increasing drowning risks in the treacherous Channel waters. French maritime authorities step in selectively, handing out jackets when small boats appear unstable or overloaded, particularly with families and children aboard. Once migrants are intercepted mid-Channel—often escorted partway for safety—the jackets are reportedly collected and returned for reuse in future incidents. This recycling approach aims to minimize waste while prioritizing life preservation over outright blockage.

Yet the controversy deepens with claims that these jackets come equipped with tracking technology, allowing real-time monitoring of movements. Skeptics argue this setup turns the aid into a sophisticated surveillance tool: positions are tracked from launch points on French beaches all the way until UK Border Force vessels take over near the median line or in British waters. Detractors claim it creates a controlled corridor, where crossings are “managed” rather than stopped, effectively guiding migrants toward UK shores under observation. This has fueled accusations that French efforts prioritize reducing fatalities over enforcing borders, while British authorities end up handling arrivals that could have been prevented earlier.

The Channel crossings remain a persistent flashpoint. In recent periods, thousands have made the journey annually, with numbers fluctuating based on weather, smuggling tactics, and bilateral agreements. Overcrowded inflatable boats, often launched from areas like Gravelines or near Calais, carry dozens at a time, including vulnerable groups. French police employ various tactics—such as beach patrols, interventions in shallow waters, or even more aggressive methods like nets in trials—but complete prevention proves elusive due to legal constraints on high-seas interceptions and the sheer volume of attempts.

Public anger in France boils over from perceptions that national resources are indirectly supporting irregular migration. Critics point to repeated instances where jackets are handed out moments before departure, followed by escorts that reduce risks but don’t halt progress. On the UK side, arrivals trigger asylum processing, detention, or returns under evolving pacts like “one-in, one-out” pilots, which aim for balanced exchanges but face implementation hurdles.

The core tension lies in balancing humanitarian imperatives against border security. Providing tracked life jackets may save lives in the short term but raises profound questions about sovereignty, control, and the incentives driving desperate journeys. As crossings continue amid calmer seas and warmer months, the debate rages: is this compassionate pragmatism or a flawed system enabling the very problem it claims to mitigate? The beaches of northern France have become theaters of both tragedy and controversy, with no easy resolution in sight.

News

Wife’s Chilling Desk Discovery: Hidden Camera Exposed Before Husband Vanished on Doomed Fishing Trip – What Were His Employees Hiding?

In a case that has gripped Southwest Florida with unanswered questions, the disappearance of two men during what was supposed…

Taylor Swift’s Secret Birthday Gift to Travis Kelce’s Niece Just Got Even Sweeter – Uncle Travis Took Her Swimming to Try It Out!

Taylor Swift has once again proven why she’s adored not just for her music, but for her genuine warmth toward…

Mahomes Magic Multiplies! Patrick and Brittany Throw Golden’s Dreamy First Birthday Bash — And Shock Fans With Baby No. 4 Reveal Next Year! 🌟👶

In the midst of a tough NFL season where Patrick Mahomes faced an unexpected injury setback and the Kansas City…

“I Couldn’t Sleep at Night”: Travis Kelce’s Mom Breaks Down in Tears Revealing the Dark, Sleepless Days Before His NFL Glory

From the anxious rookie who dreaded bedtime to the undisputed king of the tight end position, Travis Kelce’s journey has…

Tom Brady Drops Bombshell: How Gisele Divorce ‘Drained’ Him During Brutal Final NFL Season

Tom Brady spoke out about how his divorce from Gisele Bündchen made the final year of his NFL career rough….

Brenda Blethyn Drops Bombshell: Living in Separate Flats from Husband After 15 Years – And It “Works Brilliantly”!

Vera star Brenda Blethyn has revealed that she and her husband live in separate flats. The actress – who is…

End of content

No more pages to load